Molding a Mermaid

This is the 11th excerpt from my biography of Esther Williams. You can find the other entries here. In the previous post, Esther toured MGM, met with studio head L.B. Mayer, and finally said yes to giving MGM a try. In this section, Esther begins her training period at the studio as everyone attempts to figure out what a movie mermaid actually is…

Molding a Mermaid

MGM offered Esther Williams the usual contract given to most new actors. (Unlike today’s “package system” when personnel and actors are contracted for individual projects, the studio system used multi-year contracts, typically seven years, for nearly all of its creative personnel. This tied actors to specific studios, though loan-outs could be arranged, and put most of the power in the hands of the studio rather than the individual. A Fortune article about MGM written in 1932 discussed this unique multi-year contract system: “In the cinema industry, no one of any consequence is employed without a written agreement of some sort. This is partly because the traditions of the industry are not those of banking, but much more because a company which gets a Jean Harlow wants to keep her and, conversely, Jean Harlow needs to be sure that a quick shift in public taste – or the suicide of her husband – won’t stop her paycheck.”) Yikes.

But a barely 20-year-old Esther was amazingly self-assured and determined in the face of MGM’s awe-inspiring and intimidating machinery. She requested two unusual additions to her contract: one, a pass to the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel so she had someplace nice to swim, and two, an unheard of nine-month training period before her movie debut. The latter request shocked MGM; although it was typical for the studio to groom its stars and train them throughout their careers, Esther was unique in asking for such a long incubation period. She knew that a bad first performance could easily become one’s only performance, and despite MGM’s long pursuit, she doubted her own movie star potential. (Perhaps the dismal prediction of the 20th Century Fox casting director still rang in her ears). She recognized she was a complete novice, and she wanted time to take acting classes and to familiarize herself with the basics of movie-making. Nine months was pleasingly symbolic as a movie star’s gestation period, though it was too long for MGM’s liking.

But the studio eventually acquiesced. Before Esther signed the contract, though, she visited her crooked agent, Roger Marchetti. She didn’t want him to take 20% of her MGM earnings, so she convinced him to tear up the contract she’d signed back in 1939, long before the Aquacade or MGM. With that important business concluded, she signed with a new agent, Johnny Hyde, a William Morris executive who had worked closely with MGM to bring Esther to the fold. They returned to the studio, and in October 1941, she finally became a “contract player” at MGM with a weekly salary of $350 (about $6,000 today.) It was less than the $500 she’d made every week at the Aquacade, but she wasn’t the star now.

And so the clock started on Project Make-Esther-A-Star. Every day, she swam laps at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and then drove to MGM in her new Dodge coupe, her one splurge after she signed the contract. (Johnny Hyde told her that she had to keep up appearances and couldn’t take the bus anymore.) Her days at the studio were filled with classes designed to make her into the next big thing. Fortunately, MGM was very well-equipped; after all, the studio turned talented but unskilled amateurs into dynamic entertainers and stars all the time. As Debbie Reynolds remembered of her time at MGM:

You never stopped studying. Ballet, tap, modern dance. Placing the voice properly; how to sing; how to walk and move; how to model, how to hold your hands, how to hold your head, knowing the angle right for the camera; how to do makeup, how to do hair… Anytime you walked on the lot, there was activity, and often music… If you didn’t like it, you had to be bananas. If you didn’t learn from it, you had to be a moron.

Esther wasn’t a moron, and with the help of the excellent teachers at what she called “MGM University,” she began the metamorphosis into ESTHER WILLIAMS!, the movie star who would act, sing, dance, and strut across the screen with self-assured ease.

Esther took acting lessons with Lillian Burns, diction lessons with famous voice coach Gertrude Fogler, singing lessons with Harriet Lee, and movement classes with Jeannette Bates. Burns taught Esther how to break down a scene, Fogler worked to eradicate Esther’s slight “Kansas” accent inherited from her parents, and Lee reassured the nervous actress that no one expected her to be the next Judy Garland. With Lee’s help, Esther was expected to make the most of whatever voice she did have, and perform creditably when necessary. (In fact, Esther would sing quite frequently in her movies).

Jeanette Bates, the resident movement and dance coach, started with the basics. She focused on Esther’s posture, taught her to walk in high heels, and helped the young woman learn to carry herself with the poise and elegance expected of a movie star. Bates also taught Esther the fundamentals of ballet, training that she would use throughout her career to craft her performances in the water.

During her days at the studio, she also learned the unofficial but highly codified customs of MGM, an insulated kingdom with class structures and etiquette all its own. For example, all female teachers and actresses were addressed as Miss. The rule applied to the newest starlets all the way up to the most illustrious on the lot: it was Miss Garbo, Miss Hepburn, and now Miss Williams, never Mrs. Kovner or Esther. But this universal title belied the hierarchy that carefully separated mere featured players from stars. To maintain this order, the costume and makeup departments had vastly different areas for extras, contract players, and stars, with the luxury and privacy increasing as one moved up the pecking order.

Esther learned MGM’s courtly code quickly and recognized that stars were the royalty in this world and deserved respectful adulation as well as privacy. The only place where the anointed mingled with the humble peasants of this moviemaking fiefdom was in the studio commissary, and it was here more than anywhere else that Esther was reminded of the extraordinary turn her life had taken. Grabbing lunch at the studio might mean seeing Lana Turner and Robert Taylor dining on sandwiches together, or sitting near Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. Esther was shocked to watch these legends “eating and talking, just like ordinary people.”

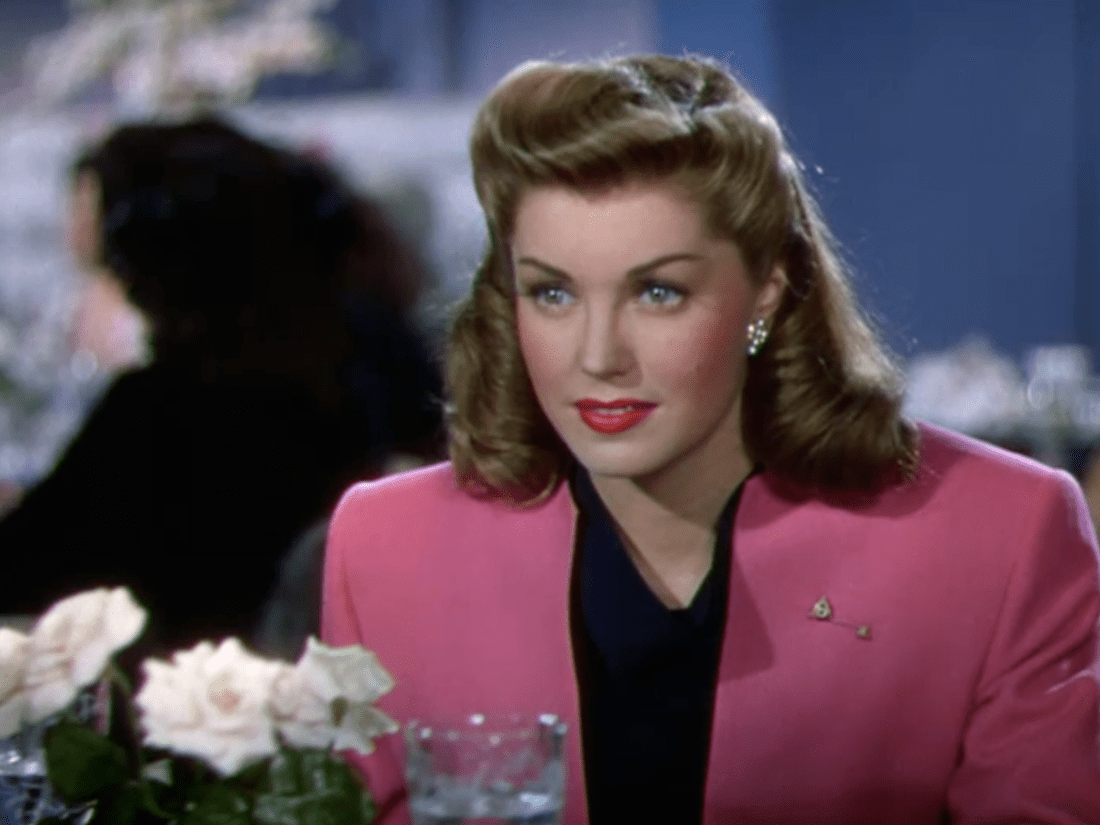

These meals at the commissary were more than just starstruck staring sessions, though. They also inspired Esther to pour everything she had into her lessons. Watching gorgeous, glamorous Lana Turner reminded Esther that even though Lana was now a blonde goddess, not too long ago she had also been a normal (brunette) teen. Julia Jean Turner had taken the same classes Esther was taking now with many of the same teachers, and to Esther, Lana’s transformation was “proof positive that the system worked. She was the perfect product of the factory…a bona fide graduate of MGM U, if not its valedictorian.”

Between Esther’s laps at the hotel pool, afternoons spent in studio projection rooms studying films and actors, endless photo sessions in the MGM portrait studio, and her movie star classes, she also found time to give swimming lessons to other MGM stars on the backlot, reportedly teaching Ava Gardner, child star Dickie Hall, and teenaged Virginia Weidler, among others.

But perhaps Esther’s most memorable and legendary afternoon was when she made a screen test with Clark Gable, the King. Carole Lombard, Gable’s wife, even came to watch, and Gable, who clearly didn’t know his lines and didn’t care, instead spouted some nonsense and planted three kisses on an astonished Esther. She remembered that as Gable walked away with Lombard on his arm, he told her, “Well, baby, I told you I was gonna kiss me a mermaid today.” And so Gable, according to Hollywood lore, was the first at MGM to christen Esther a “mermaid,” a name which immediately stuck.

The Mermaid’s Image

As Esther learned how to be a movie star, MGM began introducing their Mermaid to the public via its powerful publicity department. Although it never appeared on screen, the publicity department was one of the most important at the studio. Run by Howard Strickling, it was a key element in the creation of stars and in damage control, functioning as both a newsroom and a public relations firm. The department handled press releases and interviews, built up new stars and movies, and liaised with fan magazines and gossip columnists. Additionally, each star was assigned a personal publicist who arranged and oversaw interviews and public appearances, and also helped handle tricky or embarrassing situations that might arise for their star. Strickling’s staff stayed busy, since there were about 300 correspondents assigned to Hollywood, including one from the Vatican, which made Hollywood the third largest news source in the United States behind Washington and New York.

Beyond ordinary public relations work, the masters of spin in the publicity department seemed capable of making anything unpleasant or damaging go away. In Scott Eyman’s book, The Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer, he wrote of the publicity department: “Abortions were magically transformed into ‘appendectomies’ and alcoholism into ‘exhaustion.’” Even major accidents and deaths were professionally handled, with MGM stars told to call Strickling before they dialed the police. As Esther said of her time at the studio “We lived under the protection of the great god Public Relations, because the studio had set it up that way, with a kind of army all around us to keep scandal out of the papers.”

MGM, as well as the other studios, had close relationships with outside police departments, who would call the MGM police force if something involving a star came up. With Strickling’s help, the MGM officers were almost able to handle things in a way beneficial, or at least not damaging, to the studio. The great god’s power seemed endless, and the department was so good at creating a new or prettier reality that it can be difficult, if not impossible, to ferret out where the truth lies beneath the shimmering facade.

But MGM’s glamour machine, bolstered by Strickling’s staff, could be a very comforting place to be for the stars. Ann Rutherford remembered that MGM always took care of its people: “Warner Bros. wouldn’t—they were always spanking somebody or selling them down the river. From the time you were signed at MGM you just felt you were in God’s hands.” MGM protected its stars, but also demanded a great deal in return. Very little was off-limits to the studio, and their stars’ private lives were the property of MGM. Esther would learn this all too well during her career, but for now the publicity department was focused on crafting the perfect image for the studio’s mermaid.

Esther spent hours in front of the cameras at the MGM portrait studio and on location posing for photos the studio would send out across the country. She posed in the hot new fashions and appeared in a variety of wholesome poses and activities that range from the almost plausible to the ridiculous: reading, cuddling her cocker spaniels, brushing her teeth, dabbing on perfume, playing darts, knitting, laying in a pile of hay, fixing a lamp. She appeared in the requisite seasonal and holiday photos, too: she wears a bathing suit and a pointed witch hat for Halloween, appears in a short Pilgrim dress with buckled hat, rifle, and turkey for Thanksgiving, and dons a midriff-baring Santa suit trimmed in fur for Christmas shots with a fake reindeer.

Those braids aren’t real…

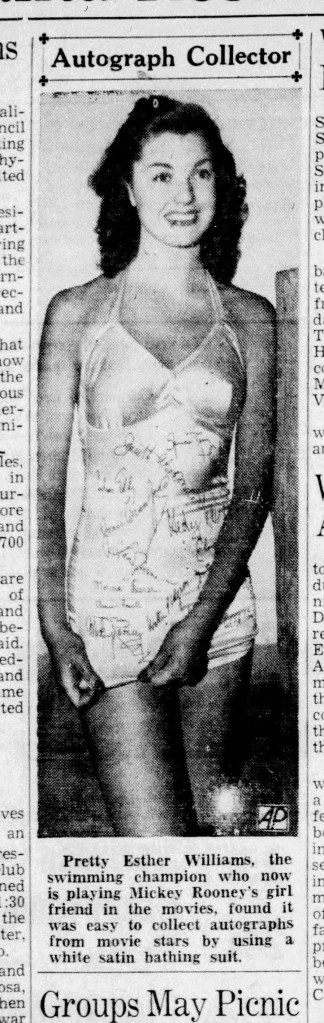

Someone in the publicity department decided to turn Esther and a white satin bathing suit (an unflattering nightmare for anyone except for Esther Williams) into a human autograph book on the MGM lot. Photos of Esther wearing the scribbled-on and now absurdly valuable one-piece appeared in papers across the country.

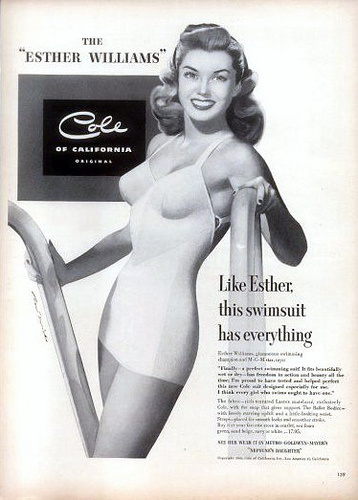

Of course, this was just one of many bathing suit shots of the swimming star. Cheesecake shots were nothing new, and were required of nearly every actress, but MGM went wild with shots of their mermaid. Esther remembered being photographed in bathing suits doing just about the studio could imagine. She must have spent days and days in the studio portrait studio and at the beach to provide fodder for the papers and fan magazines.

Yet of the thousands of photos, not one includes Esther wearing her eyeglasses. She was terribly nearsighted and must have worn her glasses constantly in real life, but MGM kept the image of a bespectacled mermaid out of the papers. In fact, we only know Esther wore glasses because she mentions it in her autobiography and it comes up occasionally in other auto/biographies; for example, Joe Pasternak mentioned in his autobiography that Esther was “so near-sighted that her own hand goes out of focus without her glasses,” but added in parentheses that “She is one of those girls who, if anything, look even more attractive with glasses.”

Very, very rarely something surfaces in contemporary accounts; for instance, a 1947 Modern Screen feature mentions that her husband “snitched Esther’s glasses—she’s on the nearsighted side” in order to pull off a surprise party at a restaurant. He returned her spectacles once they were in the private dining room so she realized that the fuzzy group of strangers were actually her friends gathered to celebrate her birthday! The lack of pictures of Esther wearing glasses isn’t terribly surprising given the era’s silly prejudice against the things and the studio’s control of their stars’ images, but in this paparazzi/instagram-crazy age, such erasure of a key part of someone’s look would be impossible.

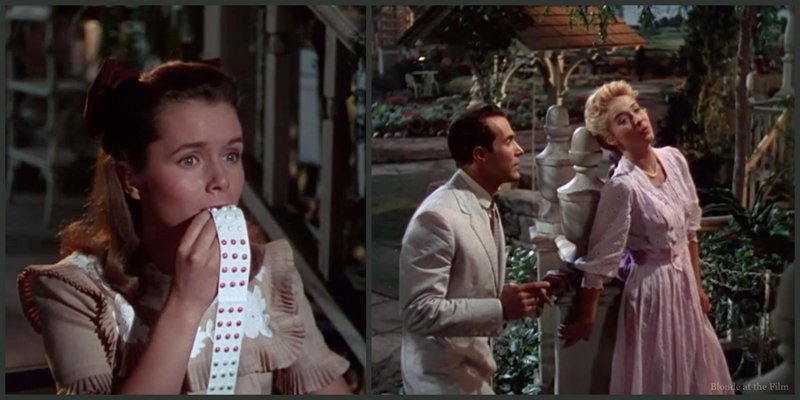

As this was the height of WWII, MGM also frequently sent out items about Esther supporting the war effort. A Sunday insert in The Los Angeles Times entitled “Spring Styles” cleverly combined the two with several photographs of Esther and Frances Gifford, another “MGM player” modeling “Home Front Fashions” while serving the war effort. (Two years later, Gifford would appear with Esther in Thrill of a Romance (1945)). Esther knits for the Red Cross in a “powder blue crepe suit dress…embellished with a blue lace dickey with a decorative jabot,” buys war bonds in a “spring suit in navy blue with braided navy lapels,” packs spare books to send “to the boys in service” in a fetching apple-green suit with “appliquéd grape designs,” and “dressed in a smart print suit” puts a service flag in the window. In another photo, she holds a basket of vegetables in support of Victory Gardens.

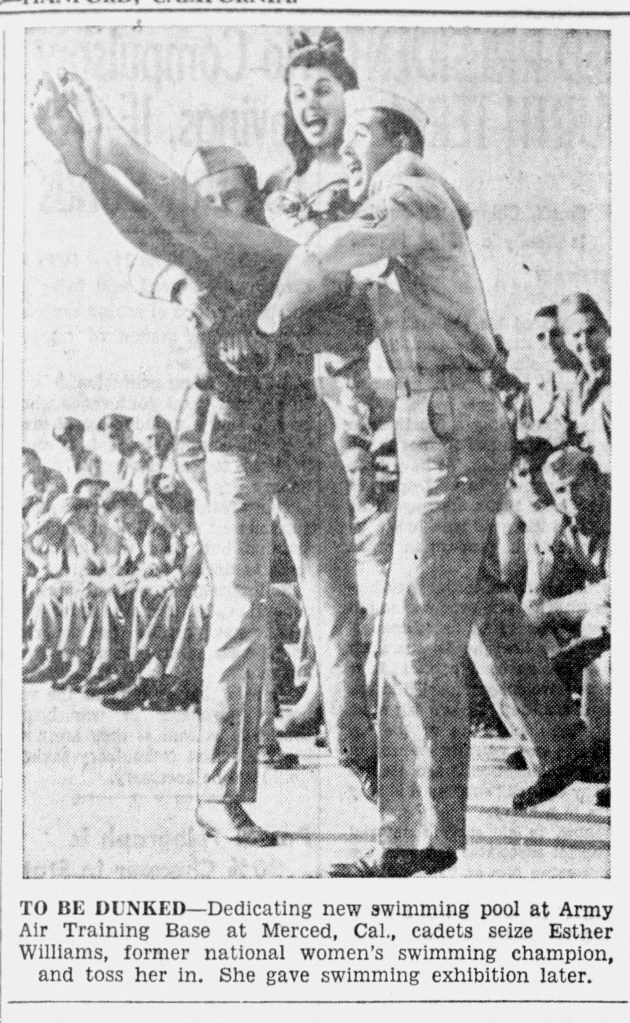

She also appeared at bond rallies and other events supporting the war effort. For example, she was a celebrity judge with other starlets at the Southern California War Workers Golf Tournament at the Inglewood Golf Club in March 1943, and she took part in a swimming exhibition with her old friend Weissmuller as part of the San Bernardino Victory Golf Tournament that raised funds for the area’s three Army bases.

And in May 1943, she visited an Army air base in Merced, CA, to inaugurate their new swimming pool. She wore a pretty tropical print two-piece with a huge matching hair bow, and posed for plenty of pictures. She even allowed two cadets to throw her into the water! Then she gave a demonstration of her fancy Aquacade-style swimming, and challenged two airmen to a swim meet to officially christen the pool (she won.) One account of the visit praised Esther for her “natural beauty which doesn’t come off in the water,” and claimed that “What Hollywood—as well as the Army—needs are more genuine entertainers like Esther Williams!” Her studies at MGM University combined with her natural charisma made her a powerful presence, and this was the first of many such visits to military bases and hospitals.

MGM funneled the photos and articles out through United Press and the Associated Press, and padded fan magazines like Photoplay and Screenland with pictures and gossipy tidbits about Esther in the summer of 1942 before she’d ever appeared on screen. This wasn’t a new nor rare strategy; indeed, the studios did this for most of their new talent in the hopes of creating buzz and gauging the aspiring star’s appeal. One comes across plenty of “stars of tomorrow” features and studio-planted publicity about actors who appeared in one or two films but never made it big. Esther was often pictured with four or five other starlets in modeling layouts and other articles, but she is almost always the only one who became a star.

But unlike most aspiring stars, Esther wasn’t a true “unknown”—which perhaps explains why she didn’t emerge from the studio’s chrysalis with an entirely new look or new name. Starlets who signed a contract were often immediately re-made (see Norma Jeane Baker, Margarita Cansino, Jane Peters, or Suzanne Burce*) with new names and altered appearances, but Esther was left unbleached and mostly unaltered. It seems that even MGM, master of makeovers and creator of stars, knew better than to mess with Esther’s bouncy brunette curls and high-wattage smile. And since they hoped to capitalize on her sports page and Aquacade notoriety, they needed to maintain a connection to Esther’s past.

So MGM trumpeted her championships and headlines and captions such as “Swimming champion turned actress,” “Swim Champ Starlet” and the epithet “swimming champ” follows her name for the first few years of her movie career. For example, a photo of Esther with her two cocker spaniels was headlined “Swim Champ a Film Star,” and the brief article began with “Remember pretty, dark-haired Esther Williams who a few years back raked in the swimming championships one after the other? Well, today she is very much in the movie swim, heading for top roles.” And one of her first public appearances as an MGM starlet was as a guest of honor at the opening ceremonies of the Los Angeles Swimming and Diving Championships at Olympic Stadium in September of 1942. Her beauty and her athleticism were joined early and often even when championship titles weren’t mentioned: a “friend” of Esther told a columnist that the starlet was often “prey” to “‘beach wolves,’” but her athletic ability always won out:

These fellows follow all the pretty girls around, playing the hero part. But they get fooled when they start following Esther. She swims out a mile or two, and they get tired. Then she has to drag them in. ‘But I always let them down at the breaker line so as not to embarrass them,’ added Williams.

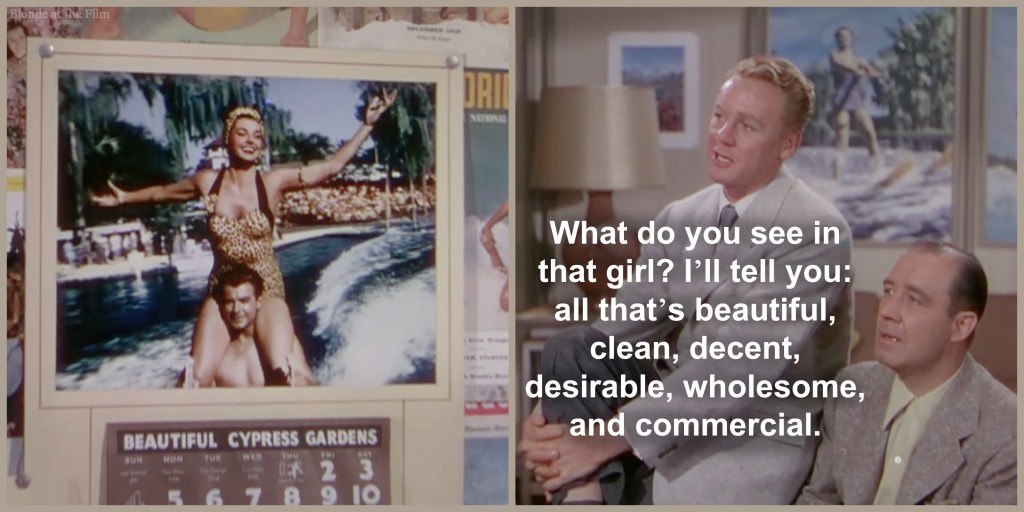

Similarly amusing anecdotes appear frequently, and though their veracity is certainly questionable, what’s noteworthy about these stories is that they link Esther’s gorgeousness to her athletic prowess and strength. Esther’s athleticism isn’t minimized nor explained away; instead, it’s celebrated. This was quite unusual, and the press recognized it. One gossip column even compares her to Weissmuller, noting that MGM plans to make her into a “female Tarzan” to replace Weissmuller, who had just left the studio to go to RKO. (Ironically, the co-stars of the Aquacade would never swim together onscreen: Weissmuller’s sixth and final MGM film, Tarzan’s New York Adventure, was released in May 1942.) And another article describes Esther as an exception amongst glamour girls; all the new starlets take cheesecake shots in bathing suits, but Esther is an “anomaly” because she is a “bathing beauty who swims!” Screenland echoed this combination of beauty and strength, telling its readers that they “might as well get acquainted because you’re going to see quite a bit of [Esther]” who “looks luscious in a bathing suit (women drool with envy when they see her figure, men just drool) and she swims like an authentic mermaid.”

Her identity as an extraordinary athlete (who was also gorgeous, don’t forget!) stayed with her, and her body was used and filmed in ways that no other star’s was, making her unique in the pantheon of movie stars. At 5’8, she towered over nearly every female star except Ingrid Bergman, and although Esther was enviably endowed, she never approached the almost cartoonish proportions that made other stars appear one errant puff of wind away from tipping over. Esther’s glamour was never tinged with vulnerability, nor was she appealingly fragile; too much strength and confidence emanated from her champion’s body.

And although every pretty starlet was occasionally dressed to thrill and titillate, especially during the 1950’s “mammary craze” with busty actresses like Jane Russell, Marilyn Monroe, and Jayne Mansfield, no other star was so alluringly put on display while performing athletic feats. Fantastic dancers like Ann Miller and Eleanor Powell come close, dancing in sparkly leotards as the audience marvels at their fast feet and terpsichorean abilities. But they weren’t glamour queens or leading ladies. Esther’s closest peer, Sonja Henie, skated in short skirts and delighted audiences with what her body could do, but there is a big difference in Henie leaping and twirling on the ice from a distance and Esther cutting through the water in a bikini in close-up. Besides, Henie was a different type of star. She was cute and adorably blonde with a charming accent, but not stunningly gorgeous as Esther was, and she was never positioned as a pin-up girl.

Esther became a movie star because she was beautiful and charismatic, yes, but also because she was strong and physically gifted. Only Esther combined the highest levels of athleticism and training in an sport while looking like a modern Aphrodite, and being marketed as one, albeit a wholesome, All-American love goddess. As gushing fan magazines wrote, Esther “has a freshness of appearance that sets her apart from the average Hollywood beauty,” and “I never saw such an alive, vibrant girl. She seems to glow all over…” Even amongst the movie studios’ carefully groomed smorgasbord of loveliness, she was unique. MGM, fortunately, knew better than to try to fit Esther into one of their molds.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for the next excerpt!

*Better known as Marilyn Monroe, Rita Hayworth, Carole Lombard, and Jane Powell.

Categories: History