The Mermaid and Me

So. It has been over five years since I posted anything on The Blonde at the Film. That is wild, and a little embarrassing. I did not mean to take such an extended break. Since I started this blog, I met a boy, got married, moved a few times, and had three children. (They are the joys of my life, but wow, they have taken up a lot of my time!) I also started working more seriously on a book, which is what brings me back today.

Once the kids came along, the book moved to the back burner, or more accurately, the stove of a friend who lives in another state. But now I want to start cooking again. Rather than work in isolation, as I have been, I have decided to share excerpts on my blog. I keep thinking of that lovely Margaret Atwood quote: “If I waited for perfection, I would never write a word.” Replace “never write a word” with “never show it to anyone,” and you’ll understand where I am.

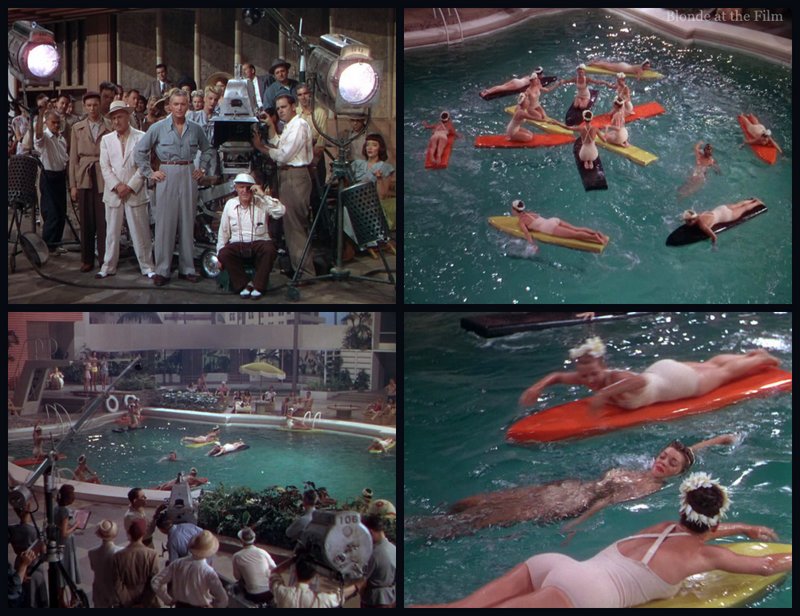

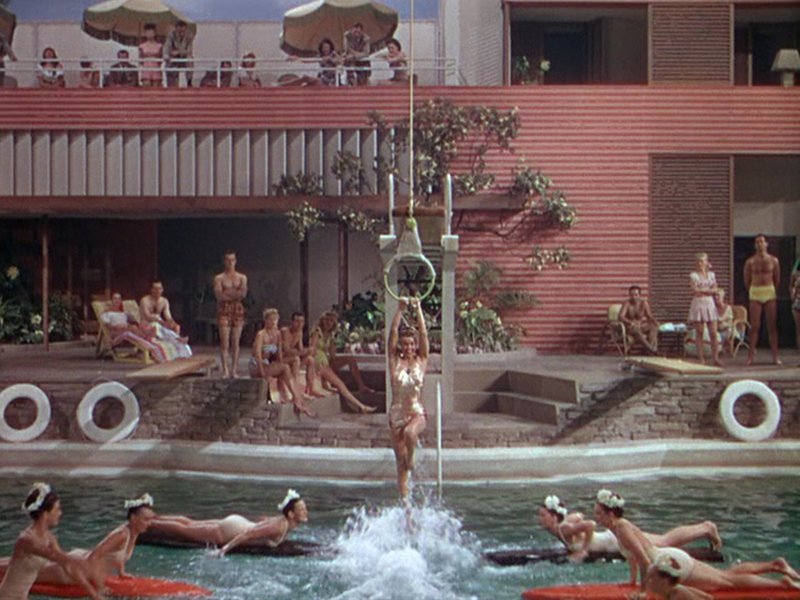

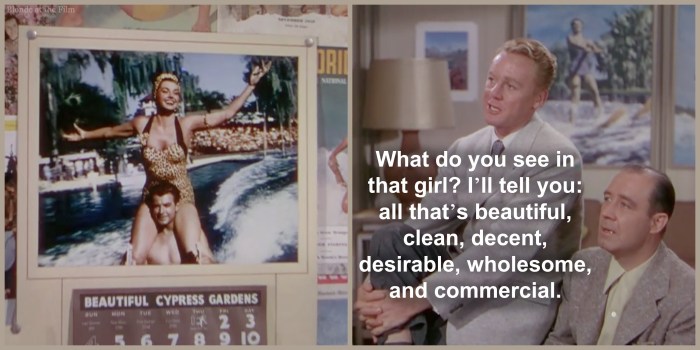

The book is tentatively titled Neptune’s Daughter: The Mermaid and Me. It’s a biography of Esther Williams with special attention paid to her films and her star image. If you’ve ever perused this site, you know that Esther and her movies are particular favorites of mine, and that I also think she has been quite regretfully overlooked. Sure, her movies are “fluff” and “escapist” and not critically acclaimed Academy Award recipients, but she and the MGM machine brought synchronized swimming to the masses. She survived and (mostly) thrived in a time and context that destroyed many other actresses, and she was (and remains) truly unique and irreplaceable in the constellation of stars. She is also an amazing window into the studio system and MGM in particular. Her movies could only have been made at that studio during that time, and I love explaining why.

Esther’s story is pretty unbelievable—an Olympic caliber swimmer-turned Aquacade star-turned MGM box office golden girl. She was a fearless athlete, an entrepreneur, a de facto producer/director, a singer, model, movie star, wife, mom, and savvy businesswoman. She was gorgeous, smart, strong, and utterly bewitching onscreen. And I think more people should know about her and appreciate her. (But didn’t she already write her story? Why, yes, thank you for asking. She wrote a wonderful autobiography, which is a valuable source. But there is more to say, more stories to tell, and different angles and lenses through which to view her life and her movies.) So here we go.

Excerpt 1 from Neptune’s Daughter: The Mermaid and Me.

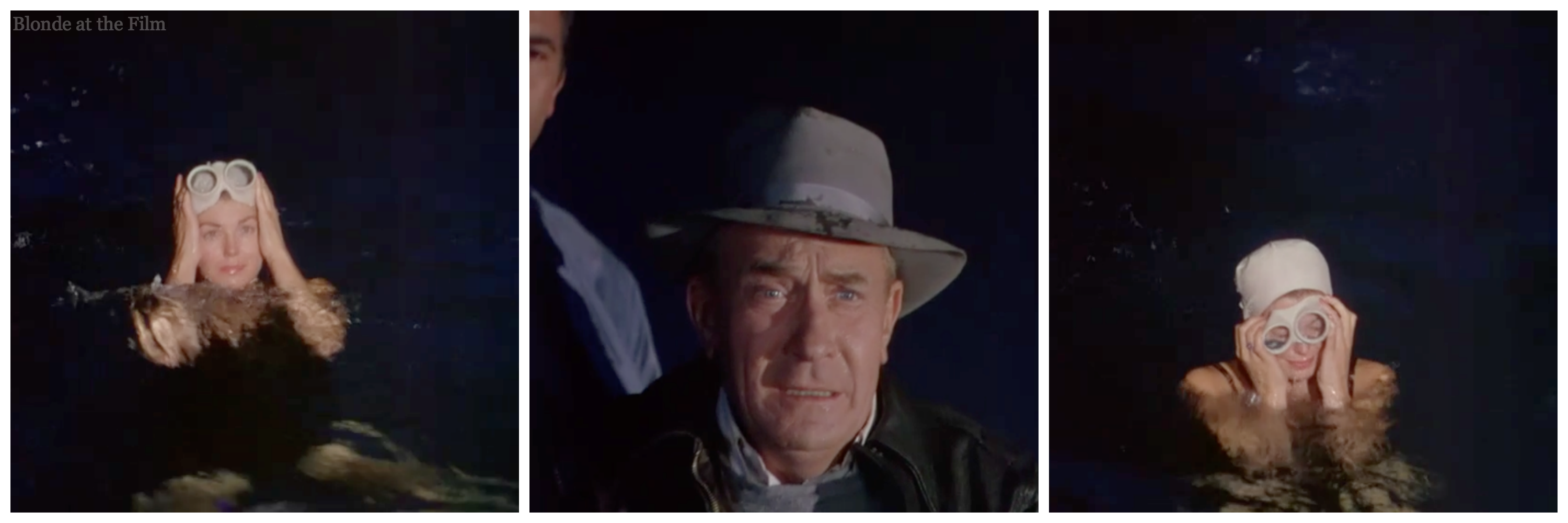

Esther Williams stoically positions her huge swimming goggles as she waits on a beach lit with torches. The sun still hasn’t risen when she runs into the surf wearing a black racing suit and a layer of goose fat to fight off the frigid water of the English Channel. She swims for hours, and even when her fellow competitors have given up and one has nearly drowned, she keeps going. But eventually she can barely keep her head above water, and even her coach in the rowboat beside her begs her to stop. She can’t keep going! But she does.

I first watched this scene in Dangerous When Wet when I was about seven-years-old, and it stuck in my mind. Even then, I recognized how unusual it was to see a beautiful movie star shed her glamorous finery and do something so athletic and intense. And it’s still a rare moment all these years later. Besides Sonja Henie‘s ice-skating extravaganzas, can you name any other popular blockbusters that feature an Olympic-caliber athlete showing off her skill and strength? The English Channel swim in Dangerous When Wet is pure toughness—there’s not a sequin in sight—and it puts Esther’s athleticism solidly in the spotlight. That’s what I first noticed about Esther Williams, and what still draws me to her all these years later.

By the time I found Esther Williams’ autobiography, The Million Dollar Mermaid, I was already a huge movie buff. Her book just made me worse. I was thirteen-years-old when it came out in 1999, and I’d spotted the book on my local library’s “New” shelf. I checked it out, not realizing that it would change my life. I’d started reading everything I could find about classic Hollywood when I was about eight, so I assumed that The Million Dollar Mermaid would be like the other star auto/biographies I’d read: a dark tale about how fame twisted a talented person into a mess, told without humor nor appreciation for the movies he or she had made. Most often, stars imbue their life stories with a sense of inevitably that goes something like this: “I was destined to be a star—my talent was undeniable and I was perfectly designed to be famous. Now let me prove it to you.” And often the studio system that nurtured, molded, destroyed, and protected the stars is treated as a minimal force, a mere annoyance, or an inconvenient authority that hindered more than helped these born movie stars reach their destiny.

But not The Million Dollar Mermaid. I was enchanted at once by the autobiography’s frankness, its humor, its sense of the ridiculous, and its self-deprecating awareness that so much of Esther’s career was based on luck: right place, right time, right smile. It told the story of how Esther, a national champion swimmer, navigated the treacherous studio system and stardom and emerged relatively unscathed. She was one of the biggest movie stars in the world for over a decade, and starred in movies that delighted audiences and brought MGM steady profits. But her autobiography is almost as much about the studio system and the business of making movies and movie stars as it is about Esther. She looked at her career, her stardom, and her life sideways with a wry smile, and she recognized more than most stars that she was a product of a system irritatingly but accurately called the “dream factory.”

The Mermaid was tall, strong, and tough, and different from the petite songstresses or cartoonishly endowed bombshells popular at the time. She was a star because she was beautiful, yes, but also because of what she could do. She was a world-class athlete and my first memory of her, the English Channel swim in Dangerous When Wet, emphasized that quality. I thought it was one of the coolest things I’d ever seen. When I watched the movie a few years later, I’d forgotten everything besides that racing scene. It was a beautiful moment of deja vu, like getting to replay a cherished memory. And it still gives me chills.

There was no one else like Esther Williams, a fact that I realized even as a little kid, and her uniqueness made her one of the most powerful actresses in Hollywood. She realized that power when she suffered a horrific injury (one of several) while filming Million Dollar Mermaid. She fractured vertebrae in her neck when a costume element malfunctioned on a fifty foot dive, and it was six months before she was healed and ready to be back onscreen. MGM halted production on the movie while she recovered; they had to—there was no one who could replace Esther. Even Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Marilyn Monroe, Cary Grant, and other greats could be replaced, and had been at some points in their career due to illness, injury, pregnancy, contract disputes, or simple scheduling issues. But not Esther! MGM had to wait on their Mermaid.

And I loved that about her—I loved her athleticism, her toughness, her skill, and her inimitable presence. I was not a “girly” little kid—I cut my hair short as a seven-year-old because I hated messing with it, and I wanted to keep it out of my eyes on the soccer field. I wore T-shirts and Umbro shorts almost exclusively, and I had no interest in bows, ruffles, or dresses (besides a Duke cheerleading dress that I wore every day for about a year when I was four. I added sweatpants underneath when it got cold.) I was curiously small and a late bloomer, but I was strong and I wanted to be a great athlete, a soccer player—this was the Mia Hamm and Carla Overbeck era.

When I looked at Esther I saw a different version of beauty far from the heroin chic of the ‘90s and the mammary-obsessed ‘50s, which seemed to be the only options. She was beautiful and strong: in one scene, Esther would wear a gorgeous evening gown displaying her sculpted shoulders and arms, and then in the next scene she would dive and streak through the water, putting those muscles to impressive use. And I thought, “That’s how I want to be.”

And so I became an Esther Williams fan. I was already set apart by my love for these movies, but my choice in idols separated me even more. I could have become one of those girls obsessed with Marilyn Monroe, for example. That’s certainly an easier idol to worship. Her face is plastered on just about anything you might desire, and she’s unavoidable in the online classic movie community. If you spend time on Instagram, tumblr, or Pinterest, it’s impossible not to run into images of Monroe, usually those painfully vulnerable late images where she looks at the lens with something like fragile desperation, or rolls around in a bed sheet. Audrey Hepburn comes in second in the image race, with Grace Kelly a close third. Monroe, Hepburn, and Kelly certainly hold a more powerful place in our cultural pantheon than Esther, to whom I add the epithet, “the swimming movie star?” followed by a hopeful pause whenever I mention her in a conversation for the first time. Compared to those three, she’s practically unknown.

I did have a Gentlemen Prefer Blondes poster—I’m only human (and blonde, for that matter)—but any further fixation was cut short when I was about ten-years-old and I checked out a biography of Monroe from the library. It started with an account of her death and the discovery of her body, so to get some respite from that dark beginning I flipped through the book to see what kind of pictures it included. I landed on a photograph of Monroe’s dead face taken by the coroner. It was black and white and horrible. Cadavers aren’t generally pleasing to look at, but I felt a visceral disgust and a heavy grief. It seemed almost unbearably sad to see her larger-than-life, glowing face sunken and abandoned. I shut the book at once and tossed it away from me on my bed.

I was disgusted not at Monroe herself, but at the publication of the image. She had been so manipulated, violated, and abused during her life that it seemed unnecessarily cruel to publish the picture of her lifeless on a slab.

That was the last Monroe biography I ever opened. In an irrational attempt to atone for the violation of that photograph, I tend to keep my distance from Monroe the star.

I didn’t go crazy for Audrey Hepburn because everyone goes crazy for Audrey Hepburn, and I wanted to be different, although I love her movies. I love Grace Kelly’s movies, too, but I didn’t become obsessed with the cool blonde because I wanted Kelly to be just as she appeared onscreen, and of course she wasn’t. She couldn’t be. I read biographies of Kelly when I was too young, I think, and the disconnect between Kelly the star and princess, and Kelly the actual person whose life was sometimes messy and sad and dark seemed too difficult to comprehend. I wanted the stunning, confident woman onscreen to be happy and strong off-screen, too, and I was afraid her movies would be ruined for me if I learned too much about her real life.

I’ve never been one to idolize suffering or long for romantic tragedy or chaos, so the long list of troubled stars didn’t attract my obsessive interest. And the cult of dead stars, particularly young, beautiful ones who die in their prime like Jean Harlow, James Dean, and Monroe, made me sad as a kid and still does today. I don’t want to fetishize darkness and pain. I’m an emotionally porous person, so to maintain my own equilibrium I realized that it was important to surround myself literally and figuratively with people who survived, who flourished, and who found some joy while they were going about the surviving and flourishing. It’s why I idolized a strong, athletic star like Esther over a sweater girl who played wimps onscreen and seemed about to tip over, or a sex goddess tragically haunted by her own beauty.

Looking back, it’s obvious why I latched onto Esther. When you learn more about her (and about many other stars—I don’t mean to suggest that she was the only healthy person in Hollywood!), it’s easy to forget that she was working and living and surviving in the same Hollywood as Lana Turner, Judy Garland, and Marilyn Monroe. Like those women, Esther was harassed, manipulated, and exploited. She too made unfortunate decisions with men and with money, and was taken advantage of by nearly everyone around her. But there was a toughness to Esther that kept these calamities from ruining her life or career, and helped her navigate the same system that seemed so damaging to other stars. As I intuited early on, and later confirmed through Esther’s autobiography and chats with her child, one of her secrets was maintaining a healthy detachment from Hollywood. She never seemed taken in by her own “stardom.” She saw how her movies fit into the giant jigsaw puzzle that was Hollywood, and she always knew that her real self was different from what was onscreen and in fan magazines, a simple but crucial distinction.

For instance, in one of my favorite scenes in Singin’ in the Rain, Lina Lamont tells Don that she thought they were engaged because she read it in a fan magazine. He tries to explain once more that they are not a real couple, and that she shouldn’t believe what she reads about herself in the tabloids. It’s played for comedy in the movie, but a lot of stars had trouble with that distinction. But Esther didn’t fall for all the glamour and the sparkle, and she didn’t lose herself in that glittering flashbulb world. She never forgot that movies are a business, a merciless industry that rewards box office success but will toss a star aside when the audiences stop coming.

The Mermaid made her own way, and I loved her for it. She has fascinated me ever since I saw her shining onscreen. I wanted to know how and why she became a star. I wanted to discover more about the infrastructure that supported the Golden Age of Hollywood. And I was deeply curious about the army working offscreen in the various specialized departments with their own policies and hierarchies: the costume departments that did far more than clothe the onscreen talent, the publicity departments that were disparaged when they “invaded” the stars’ lives but adored when they saved them from scandal, and the writers who had to keep finding new ways to get Esther in the water.

I wanted to know about the sign printers, the carpenters, the researchers, the set decorators, the animal wranglers, and the accountants who kept the cameras rolling. I wanted to know more about the backlot, and why it made more sense to build an entire New York City neighborhood in Culver City than to film on the actual street in New York.

There was so much to learn, so with the Mermaid as my guide, I set out to track it down.

*

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed it and I am excited to post more excerpts soon!

Categories: History

Congratulations on your marriage and family. I am glad to see you posting again. I did not know as much about Esther Williams, I did come across Annette Kellerman, she did a few silent movies. Talented people deserve respect and recognition, not exploitation and abuse.

Welcome back! Seeing your sender name in my email inbox was a delightful surprise, making me instantly nostalgic about your posts of yore. I haven’t even read your new post yet, but I couldn’t wait to tell you how glad I am to have received it!

Hannah M. Kerwin

Thank you, Hannah!

This is wonderful! Way to go.

Jeff

So glad you are returning to your passion!

Cannot wait to hear more about the book and pre-order! So glad to see you posting again.

Thanks so much!

Congratulations and welcome back! I’ve enjoyed reading your post in the past. My wife and I love watching pictures from the Golden Years of Hollywood. Looking forward to seeing more!

Thank you!

Wow! What an interesting, intense, informative and well-written text.

Just excellent! Looking forward to more of the same…..

Welcome back and keep up the great work

Thank you!

So glad you’re back. Reading through this post made me realize that it’s been so long since I’ve seen an Esther Williams movie 🎥 and this has reignited my interest in her.

This made my day! Thank you!