Strong Enough to Swim Pretty

This is the 5th excerpt from my biography of Esther Williams, The Mermaid and Me. You can find the other entries here.

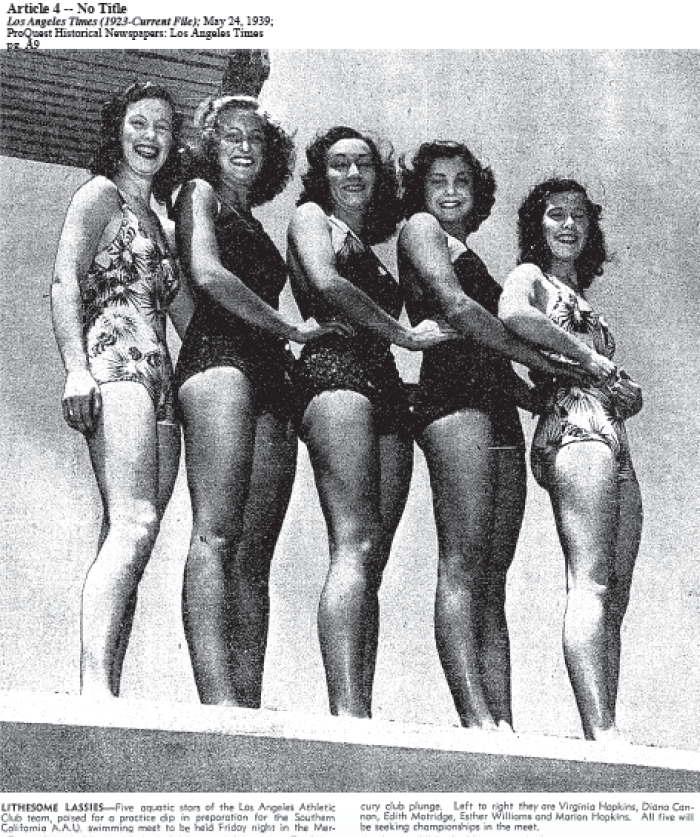

Esther Williams seemed to be a shoo-in for the 1940 Olympic team. Many of her teammates were on the list, too, and just a few weeks after their national championship victories in 1939, they swam in an “Aquatic Show” at the Olympic Stadium to raise money for the Olympic team. Photos of Esther dominate the press for this event and other swim meets that fall—she remained the very pretty face of the L.A.A.C. swim team.

Over the next several months into the spring of 1940, Esther was invited to various events as a celebrity swimmer, including a Boy Scout water carnival and the “circus day” aquatic show at the El Mirador Hotel in Palm Springs, a hotspot for movie stars and wealthy sun-seekers. She was a guest at conventions such as the Associated Women’s Students—Women’s Athletic Association Conference in Pasadena (a nice continuation of her days as an officer of the Girls Athletic Association at Washington High.) A newspaper report noted her attendance, calling her “Esther Williams, well-known swimming star,” and she was asked to demonstrate her unique butterfly stroke.

Esther and her teammates kept competing in preparation for the 1940 Olympics, which had been moved from Tokyo to Helsinki after the outbreak of war in Asia in 1938. Esther competed in swim meets in early 1940 and went to Miami in March for the national indoor championships. But the domination that Esther and the L.A.A.C. had enjoyed for the last eighteen months came to a disappointing end. The relay team of Williams, Motridge and Hopkins came in second. The L.A.A.C. struggled as a team, and placed an uncharacteristic 4th in the team competition.

Even more surprising was Esther’s individual performance. She failed to advance to the finals of the 100m freestyle, the race she had won at the National Championships the previous July. One of the Los Angeles Times articles about the swim meet highlighted her poor performance with the headline “Local Girl Eliminated from Meet,” which probably didn’t boost her spirits.

These results nearly brought me to tears. I was hugely disappointed to see the Mermaid’s name fall from the 1st place columns. I wanted her to keep winning! I wanted her to go out on top, to end her swimming career as a champion. But she didn’t even make the finals! What happened? Unfortunately, stark newspaper reports and result columns don’t explain why the L.A.A.C. and Esther were so off at this meet.

This was a disappointing but also very confusing swim meet to discover because the newspaper accounts differ so completely from the story that Esther recounted in her autobiography. Overall, that book seems very accurate, but not when it comes to the National Indoor Championships in March 1940. In The Million Dollar Mermaid, Esther and writer Digby Diehl recount an upsetting story about Aileen Allen betraying Esther and keeping her from competing in the Pan-American Games. According to the autobiography, and to most other bios of the star, Esther’s performance at the 1939 National Championships earned her an invitation to the Pan-American Games held in early 1940 in Buenos Aires. Esther was looking forward to her first international competition and was thrilled to travel to South America.

But her invitation never arrived, so she assumed that they had chosen another swimmer, though it seemed odd. When she arrived in Miami in March, Esther met up with some swimmers who had just returned from Buenos Aires. They told her that they had missed her, and they asked her why she hadn’t accepted the invitation to compete. Esther immediately confronted Allen and learned that her coach had withheld the invitation because she was afraid that the excitement of an international meet would have interfered with Esther’s training for the Miami championships and the Olympics.

Esther was devastated at her coach’s actions. She and her teammate Edie Motridge, who was infuriated on Esther’s behalf, refused to swim in the meet and they returned to Los Angeles on their own.

Or so the story goes in Esther’s autobiography. That version of events seems to have relied heavily on a 1946 Modern Screen story that sprawled across the May and June issues detailing Esther’s pre-movie star life. The story has been around for a long time.

But it has some major flaws. First, there was no Pan-American Games in 1940! In late 1939 and into the spring of 1940, the American Olympic Committee and the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) did discuss holding Pan-American games in the US in the summer of 1940 to replace the Olympics, but the plans never materialized. Later that year, a Pan-American Sports Congress was held in Buenos Aires, but that was just a meeting in which delegates planned and organized the first Games. The inaugural event was scheduled for 1942, but those plans were scrapped once WWII engulfed the globe. In fact, the first Pan-American Games weren’t held until 1951. So that’s a problem.

Second, there are multiple newspaper accounts detailing Esther’s and Motridge’s performances at the Miami meet. The result columns contradict the story that the two young women left without competing.

I’m not sure what to do with this story. It’s a big thing to invent, and it’s an outlier in what is mostly an easily verifiable autobiography. What seems most logical to me, but still weird, is that Esther was so disappointed with her lackluster performance at the Indoor Championships that she tried to block it from her mind or find some way to come to terms with it. Perhaps Esther had heard of the Pan-American Congress, and the events became conflated in a tangled mess that allowed her to excuse her unfortunate races in Miami. Perhaps she was furious at Allen for some other reason; maybe Allen refused to let Esther swim the races that she wanted to—it doesn’t appear that Esther competed in any individual breaststroke events, for example.

Or maybe there was some sort of incident that would explain why the team failed to live up to expectations at that meet. I’d chalk it up to the memory of a woman trying to recall events from sixty years ago, but the story appears in that 1946 fan magazine recounted in startling detail, so it wasn’t just an elderly woman’s invention. (What’s strange, too, is that the writer of that Modern Screen piece didn’t verify the information. The mere existence of a 1940 Pan-American Games should have been a quick fact-check, at least!) And Aileen Allen was still coaching at the LAAC until her death in 1950, and one might assume she would object to being called out as the villain of Esther Williams’ swimming career.

But the stories ran, and Modern Screen‘s version of events, which was then echoed in Million Dollar Mermaid, has been repeated and accepted as fact for the last several decades, which makes it harder to untangle. But there it is. (And that’s why I try to verify everything with different sources…)

Regardless of this oddness, Miami marked the end of Esther’s competitive swimming career, though she didn’t know it at the time. In April, just a few weeks after the National Indoor Championships, the Summer Olympics were cancelled due to the outbreak of WWII. As you can imagine, it was a devastating development for all the athletes. Esther’s days as a champion had abruptly come to an end.

Esther mourned her Olympic dream, though she vaguely hoped to make the 1944 Games. But she was a practical person, an eighteen-year-old with a high school diploma who needed to start her adult life. College wasn’t in the picture, so she got a job as a stock girl at the upscale department store I. Magnin. At first she tried to fit in workouts around her job, but her time in the pool began to taper off. She was busy at the store, and her heart didn’t seem to be in it anymore.

Every morning, Esther rode the streetcar to Wilshire Boulevard to her job at the 141,000 square foot department store. I. Magnin was based in San Francisco and had just opened the Los Angeles branch in 1939 in an art deco building of white marble. Esther worked on the 4th floor in Sportswear retrieving and replacing items that salesgirls presented to customers. She also modeled clothes within the store (this was a time when customers could expect personalized fashion shows), and occasionally appeared in I. Magnin’s newspaper ads.

She liked the job: she made friends with her coworkers and was hoping to eventually work her way up to being a buyer. She hadn’t considered show business after her disastrous screen test the year before, though she would soon be drawn into that world.

In late April 1940, about a month into her job at I. Magnin, Esther got a phone call from an assistant to Billy Rose, the show business impresario. He was currently casting a west coast version of his Aquacade for the Golden Gate International Exhibition, a World’s Fair, in San Francisco. The pretty young national champion had caught the eye of Rose’s scouts, and they invited her to audition for the starring role, Aquabelle #1. It was the part that Rose’s wife, Olympian Eleanor Holm, played in the original Aquacade in New York.

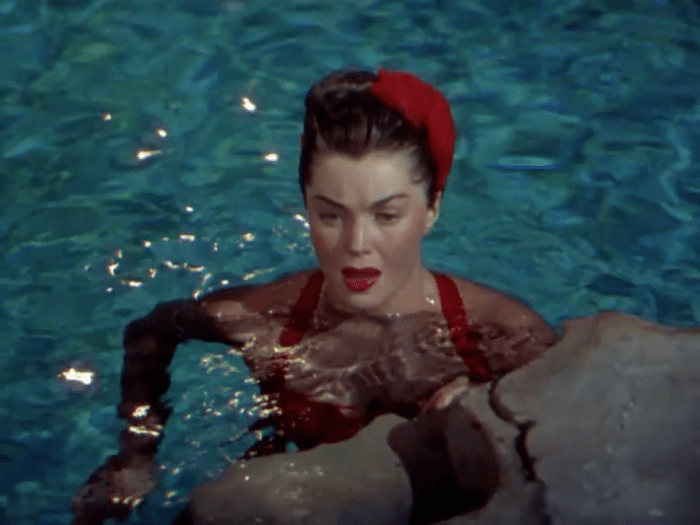

Esther was hesitant. She didn’t want to put her I. Magnin job in jeopardy for something that seemed like such a long shot. But Rose agreed to wait until Esther’s lunch hour, and the head salesgirl at I. Magnin let Esther borrow a fancy red suit from the store’s stock for the audition. She walked to the Ambassador Hotel Pool and met Billy Rose himself, who told Esther he might have something “a lot better” for her than a department store job. Then he asked her to swim.

Esther wasn’t sure what he wanted, so she dove into the pool and raced across it as fast as she could with her national champion-winning freestyle. She jumped out of the pool and stood there by Billy Rose, dripping and anxious. “You swim very fast,” Rose said. She answered, “That’s what I do, Mr. Rose. I’m a sprint swimmer. The U.S. 100-meter freestyle champion.”

He wasn’t convinced. He told her “I don’t want fast; I want pretty,” explaining that he needed swimmers who could move through the water with their heads up and their shoulders above the surface so that the audience could see them. Confident Miss Esther replied, “Mr. Rose, if you’re not strong enough to swim fast, then you’re probably not strong enough to swim ‘pretty.’” He thought that over and offered her a job. She hesitated, reluctant to lose her amateur status and forfeit any chance of swimming in a future Olympics (she had no way of knowing, of course, that there wouldn’t be another Games until 1948.)

She called her “agent,” (despite the horrible screen test and the lack of other opportunities, she was still technically Marchetti’s client). He was delighted and urged her to take the job.

Esther walked back to I. Magnin. By the time she got there she had made a decision: she would be Aquabelle #1. Esther gave her notice at the store that afternoon, and her friend let her keep the red swimsuit as a parting gift. She also helped Esther pick out a black wool skirt suit for San Francisco, and she allowed the former stock girl to open a charge account to cover the $85 price tag. Esther had been making $76 a month at the store, so this was a huge purchase.

Esther’s parents were nervous about sending their eighteen-year-old daughter to San Francisco by herself, and they weren’t sure about the whole water pageant idea, but she convinced them it was a great opportunity.

About 24 hours later, Esther was on a night train from Los Angeles to San Francisco in her own private compartment, the first time she had ever traveled so luxuriously. She felt mature and sophisticated in her new outfit as the train chugged towards San Francisco, the Aquacade, and a stardom Esther had never even imagined.

Stay tuned for the next excerpt from The Mermaid and Me!

Categories: History

I’ve liked your spoiler-rich reviews for years, going back before your hiatus, and have been very glad to see you, er, diving back in again. I trust you’ll let us know when we can get the EW book!

Thank you so much!

Wow, interesting information about the 1940 indoor national championships. I suspect that this was the first real disappointment, so she, as competitive as she was, decided to put that memory behind her. So the autobiography probably just sort of “hid” the reality. But guess what…it shows she was human! She took that poor performance and wanted to bury it.

But yeah…very interesting!! For fun I “googled” it quickly and couldn’t find anything about that meet in Miami quickly. So kudos to you for your find!!

Thank you! You’re probably right, that makes a lot of sense.

Great Story! Thanks so much.

Thank you!