Aquabelle #1

This is the 7th excerpt from my biography of Esther Williams, The Mermaid and Me. You can find the other entries here. In the previous excerpt, I set the scene for Esther’s first foray into show business in Billy Rose’s Aquacade in San Francisco. The Aquacade was due to open in the spring of 1940 as part of the second year of attractions on Treasure Island, an enormous complex built for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. You can read more about it here.

Aquabelle #1

In a Los Angeles Times article entitled “Esther Williams, Queen of the Aquacade,” the casting of “beauteous” and “shapely” Esther as Aquabelle #1, the leading lady, in the 1940 Exposition was officially announced. The article appeared on May 13, 1940, and the show opened May 25. It was a speedy turnaround, but Rose had been in show business for a long time and this was his third massive production of the Aquacade. It might seem as though the casting of his star a few weeks before the premiere was a needlessly rushed affair, but everything about the 1940 Aquacade was rushed. Rose didn’t sign the contract with the Exposition until March, and construction on the Aquacade’s new home began less than two months before the show opened. But Rose knew what he was doing. He wisely hired the New York show’s choreographer and director John Murray Anderson to re-stage the show at Treasure Island, and brought other key personnel west with him, too.

Fortunately, Esther was a quick learner. Soon the novice performer was swimming “pretty” with her head and shoulders above the water so that the audience could see her smiling face. She also picked up the basics of water ballet, and her excellent performance reinforced Rose’s decision to cast the young swimmer. He was taken with his new star, and he was extraordinarily prescient about her future. He wrote a memo to his publicity department explaining his strategy for the San Francisco Aquacade: “I want to pivot everything around Williams. It is up to us to make this girl known up and down the coast. With the possible exception of Eleanor Holm, she’s the most beautiful swimming champion in the history of aquatics.”

So despite Esther’s relative obscurity and the fame of Aquadonis #1, Johnny Weissmuller, Esther was featured just as much as Weissmuller in the official Aquacade program. A photograph of Esther gliding through the water appeared in official ads for the Fair, and it was her face that graced the Exposition schedule in various newspapers. It seems strange to promote the unknown swimmer over the movie star; after all, by the time he swam on Treasure Island, Weissmuller had played Tarzan in four successful films (he would eventually appear in a dozen). But perhaps Rose understood the lure of a lovely lady in a bathing suit trumped even Tarzan’s pull.

And so a smiling Esther in various suits and cheesecake poses appeared in papers across the country with captions like “Bring on the Heat, I’m Ready,” or the simpler “Aquaqueen.” In other ads, this long blurb “One person who’s not going to be perturbed by warm weather, no matter how high the mercury may go, is this beauty who spends a goodly part of every day swimming” accompanied pictures of the eighteen-year-old. Much of the publicity trumpeted her various national titles and records, too; this type of caption “Esther Williams, holder of three American swimming records, tossed her amateur standing off the deep end and jumped into the Rose extravaganza after it,” was common.

But it’s not surprising; the Aquacade’s combination of athletics and entertainment was relatively new, but very important to Rose, who consistently tried to hire the best athletes he could find, and trumpeted their competitive achievements in the show’s publicity. For example, Oakland Tribune sports columnist Alan Ward wrote of a conversation with an Aquacade PR man,

‘I never figured an Aquacade came under the heading of sports. I put it in the same category as a circus, a rodeo or a—’ ‘Not sports?’ the PR man shrieked, ‘How about Miss Williams? How about Weissmuller? They’re great competitive swimmers, aren’t they? And what’s swimming, if it isn’t a sport?’

Eventually, Ward conceded in his column that sports were present in the Aquacade and the Ice Follies at the Fair, and wrote that “This year extravaganzas fundamentally theatric will carry a certain sporting flavor.” Rose certainly saw the Aquacade as a combination of athletics and entertainment, and this innovation, which is also seen in the Sonja Henie movies and live shows, laid the foundation for Esther’s MGM career.

The 1940 Fair

On May 25, 1940, the Golden Gate Exposition opened for its second season. President Roosevelt officially gave the signal to turn on the lights, and the mayor of San Francisco and the governor of California were there in person to open the Fair. But Esther probably missed the festivities because she had to prepare for her first show. When the gates opened at 9am on the first day, 10,000 people were already waiting: “Lured by sunny weather, lower prices, new shows and exhibits and the chance to forget a war-ridden world for a while, crowds swarmed across the 400-acre world’s fair of the west…”

Although it must have seemed a world away from the shimmering pleasure palaces on Treasure Island, Europe was indeed at war. The Nazis had invaded Poland on September 1, 1939 about two months before the Exposition closed its first season, and in the days and weeks that followed, most European nations declared war on the Axis. In early May 1940, as Esther was rehearsing her water waltz with Weissmuller, Winston Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as British prime minister, and Germany invaded France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. And when the Golden Gate Exposition opened on May 25, the Allies were retreating to Dunkirk, and Belgium was three days away from surrendering to Hitler. The contemporary accounts demonstrate this surreal collision: for example, The Madera Tribune’s front page on May 25 was dominated by the huge headline “Allies Smash German Wedge, Nazis Claim Boulogne Taken.” Directly below the block letters is an image of Treasure Island with the caption “Treasure Island Lights Up For Opening.” Given world events, one might have thought that language such as this “As openings will, the fair on Treasure Island offer a splendid opportunity for oratory, ribbon-snapping, flag-raising and bomb-bursting” would have been deemed inappropriate…

But the war didn’t dampen the excitement surrounding the Fair, and when the gates opened, many went straight for the newly renovated International Hall and paid their 44 cent admission fee to see the Aquacade. There they witnessed an unusual spectacle unlike anything they’d ever seen (unless they’d attended Rose’s shows in Cleveland or New York, of course.) Like its predecessors, the 1940 Aquacade combined “dry” and “wet” entertainment, and melded the worlds of sport and show business.

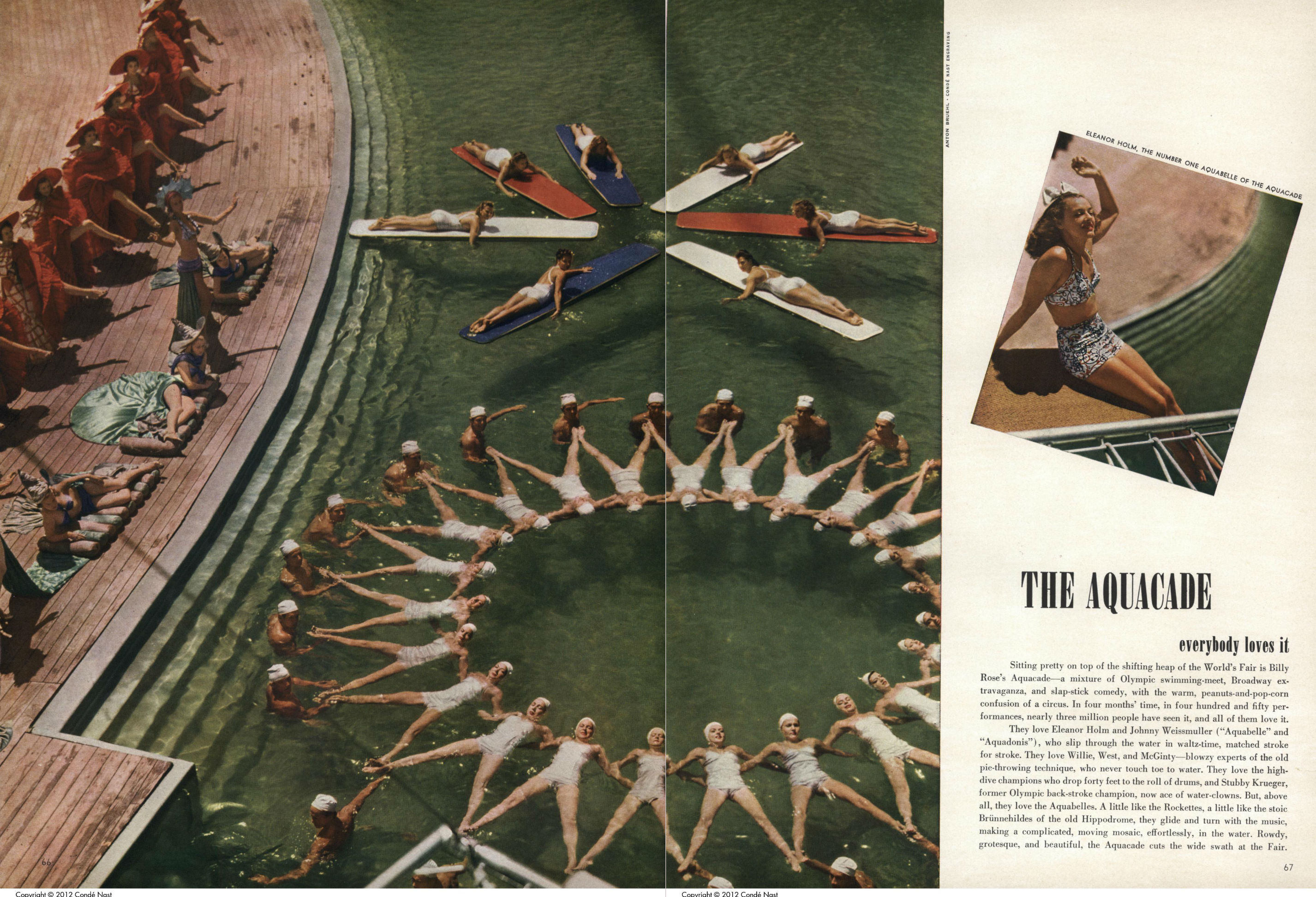

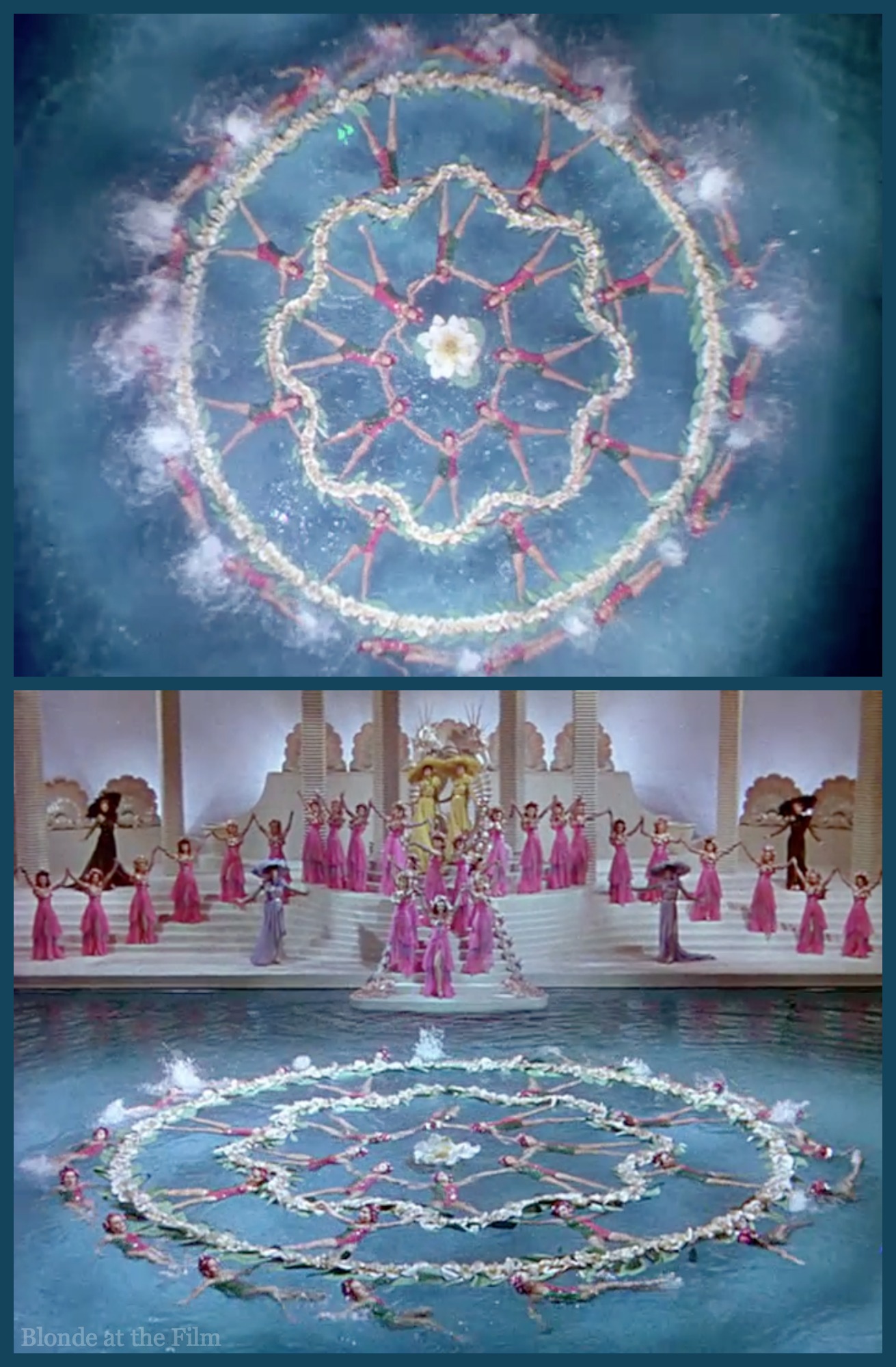

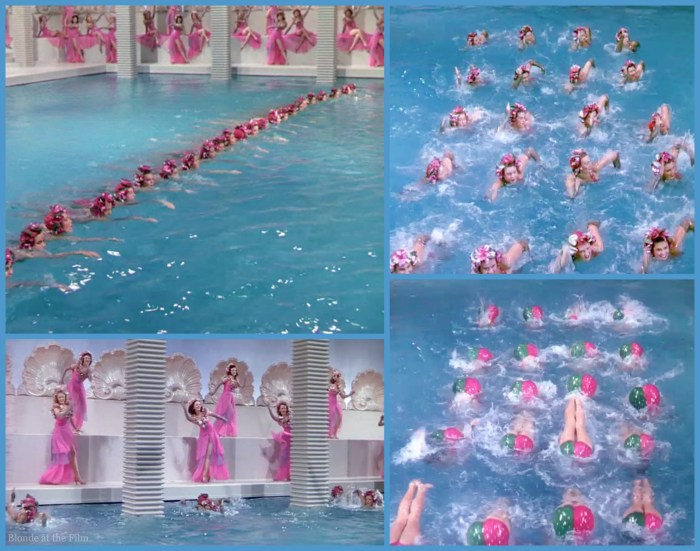

The show was divided into four acts. The first had a “California beach” theme and featured a large water ballet where champion swimmers splashed in choreographed routines along with dozens of other chlorinated chorines. Divers gracefully hurled themselves into the water from gasp-inducing heights atop two diving towers as Morton Downey, a famous Irish tenor, and the well-known Fred Waring Pacific Coast Glee Club sang with a live orchestra. The amphitheater seating allowed the crowd to appreciate the splendor and the kaleidoscopic arrangements of the aquabelles, whom Vogue described as “a little like the Rockettes, a little like the stoic Brünnehildes of the old Hippodrome, they glide and turn with the music, making a complicated, moving mosaic, effortlessly, in the water.” (The kaleidoscopic arrangements of the chorus would become a trademark of Esther’s film ballets, too, especially when overseen by the master of the body-as-geometry overhead shot, Busby Berkeley.)

The second act saw Morton Downey introduce Esther, Aquabelle #1, in a dry production number. It was typical for the swimmers to start their performances on the stage, which allowed for tame stripteases as they removed their elaborate, shimmering robes, capes, and headpieces before diving into the tank. Esther’s debut was no different. She wore a shimmering chain mail evening coat over her swimsuit, but it was Eleanor Holm’s hand-me-down, and what had been an elegant tea-length cover-up on the much smaller star barely reached Esther’s knees and refused to buckle in the front. Rose spared no expense on spectacle, but he was more than willing to skimp where the audience wouldn’t notice. Besides her too-small coat, Esther only had one swim suit, and it progressively shrunk over the months of dunking and dryings between shows.

Next, Esther wowed the crowds in a synchronized duet with Weissmuller to the strains of Strauss’s famous waltz, “The Blue Danube.” In between the water spectacles, vaudeville comedians, including pratfall wizard Walter Dare Wahl and aquatic comedian Norris “Corky” Kellam, aka the “Human Cork,” provided laughs, and Weissmuller even dried off for some land-based skits.

In Act 3, the setting changed from California to Coney Island at the turn of the century, and then the French Riviera before ending with a patriotic production number. Esther and Weissmuller led the company in the “Yankee Doodle Dandy” finale full of red, white, and blue and “chesty swimmers with their chins up.” Everything was cloaked in a dazzling array of lights, sparkle, and pizzazz thanks to Rose’s legendary showmanship, and every moment played to the rafters.

The Aquacade was presented 23 times a week: every weekday at 3pm, 7pm, and 9pm, with a fourth show added on weekends and holidays. Over 50,000 people were in the audience for the eight performances on the first weekend of the Exposition, and the Aquacade quickly became one of the most popular attractions at the Fair.

Critics and audiences agreed that the Aquacade was a must-see show. One reporter wrote, “The Aquacade is easily the finest attraction at Treasure Island, beauty and color, rhythm and motion in the water under changing lights. And too, there are chorus cuties on the tremendous stage in costume and without—in bathing suits.” Another rather poetically gushed over “the breathtaking high diving, the rib-tickling tomfoolery of the pantomime comedians,” and “The forty who swam thru inky blue waters to waltz strains…” Another review of the show noted the “scads and scads of pretty girls, unbelievably talented divers and swimmers and even funny men and a flag-waving finale.”

Esther came in for particular praise. One review hit on the miraculous quality of her swimming, calling Esther “a lovely who makes swimming seem a ridiculously easy enterprise,” a compliment that was echoed many times over her career. Ernie Pyle’s column about the Fair included praise for the young star, too. The celebrated correspondent wrote, “I saw [the Aquacade] last year in New York, and consider it one of the best shows ever put on.” He and a friend “sat right in the front row with our chins practically on the rim of the pool” and concluded that the Treasure Island Aquacade “is just like last year’s in New York.” He noted that the “West Coast equivalent of Eleanor Holm” is a “beauty named Esther Williams, and they introduce her as the most beautiful aquatic star in the world (I wonder how Eleanor likes that?).”

Of course, in a few years, thanks to Esther Williams’ MGM musicals, audiences would become accustomed to colorful water ballets with orchestras, light effects, and a chorus of synchronized swimmers, but the spectacle was still very much a novelty in 1940.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned for more excerpts from The Mermaid and Me!

Categories: History

Again more great reading!! I really appreciate your work on this! It is a fun and enjoyable read!

One quick editorial note though. In the second to last paragraph that begins with “Esther came in for particular praise”, there is a quote of Ernie Pyle that states “I saw [the Aquacade] last year in New York, and consider it one of the best shows every put on.” I think you mean “ever put on”, instead of “every put on”. Just a suggested change for your book, unless of course, Ernie actually wrote “every”.

Tim

Thanks for catching that typo!