Do it Big

This is the 10th excerpt from my biography of Esther Williams. You can find the other entries here. In the previous post, Esther tried to adjust to normal life after her summer starring in the Aquacade, and repeatedly turned down MGM’s offers of a movie contract. In this section, MGM tries to persuade Esther to become their movie mermaid, and I nerd out on the marvels of the studio system, specifically the frankly absurd but glorious world of make believe that only MGM could create.

Before getting into it, it’s important to remember that the studio system was very different from the movie business today. In the studio system, which flourished in the 1920s-1950s, movie studios kept every employee, from the biggest star to the carpenters, cooks, and composers, under contract and on salary. Today, studios operate under the “package system” and essentially everyone is an independent contractor hired for specific projects. So except in the rarest of circumstances when personnel were “borrowed” from another studio, in the “Golden Age of Hollywood,” the company that owned your contract and paid your weekly salary controlled the movies you worked on. (Which is why MGM was trying to sign Esther to a contract, not a specific movie.) This system enabled constant production and also cultivation of certain styles and genres. All the big studios (Paramount, Warner Bros., RKO, 20th Century Fox, and MGM) operated similarly, and the studio system made it possible for Esther Williams’ extravaganzas to flourish.

The Kingdom of MGM

In August 1941, MGM sent an agent in a limousine to I. Magnin. He begged Esther to meet with L.B. Mayer and tour the studio. She agreed. Her fellow salesgirls and the manager outfitted Esther in a Chanel suit and sent her off to MGM.

The studio hoped to finally hook their mermaid with a chat with the big man himself and a tour of MGM and its enormous backlot, the biggest collection of false-fronted villages, city streets, jungles, castles, and train stations in Hollywood (much of the information about the backlot comes from the excellent book MGM: Hollywood’s Greatest Backlot by Steven Bingen, Stephen X. Sylvester, and Michael Troyan.)

Esther started with Mayer, whose grand office was “designed to intimidate, from the grandeur of the anterooms, where his secretaries sat, to the mammoth walnut doors that opened the office.” Esther walked down the sixty foot, plush white carpet runway leading to Mayer’s white leather desk as he “scrutinized [her] through his thick glasses as if I were a piece of merchandise up for sale.” But it didn’t bother her—modeling at I. Magnin and her time at the Aquacade had toughened her up.

It wasn’t a terribly auspicious meeting: Mayer wasn’t a welcoming host, and he didn’t have much to say to Esther besides marveling at how tall she was (5’8). She took this as a dismissal and began the long walk to the door, but he called her back with promises that she wasn’t too tall. He and the other executives who had come to see Esther, the girl who wouldn’t sign, assured her and each other that if statuesque Ingrid Bergman (5’9) and Loretta Young (5’6) could play love scenes with much shorter co-stars, MGM could work around Esther’s height, too.

Finally, Mayer got to the point and asked Esther if she wanted to be at MGM. She said she wasn’t sure and would like to look around first.

So off she went to tour the studio. Esther was awed, as anyone would be. MGM was truly its own world, a surreal kingdom where make believe came so close to reality. Set on 167 acres in Culver City, with three separate entrances and a trolley to move employees across its immense campus, MGM was massive, self-sufficient, and powerful. If any studio was to turn a pretty swimmer into the star of swimming musicals, it was MGM, whose motto was “Do it right…do it big…give it class!”

L.B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, who was vice-president of Production at MGM from 1924 until his death in 1936, had built a successful business and brand on delivering expensive films depicting a wonderland of beauty and glamour. This was the strategy even in the studio’s early days, and usually MGM’s refusal to skimp paid off handsomely. A 1932 article in Fortune noted that the studio demonstrated that “although vast expenditure is no guarantee of good results, economy is decidedly not the secret of profitable movie production…as Mr. Thalberg observes, differences of hundreds of thousands in expenses are easily justified when they may make differences of millions in the ‘take.’”

MGM was still famous for glamour and gloss in the 1940s, and it spent more than the other studios on production. By the end of WWII, an MGM movie cost an average of $1.7 million (about $30 million in today’s dollars), nearly double the other studios’ average of $900,000 per film, but MGM’s investment seemed to pay off. In the 1944-45 fiscal year, MGM made over $22 million dollars in profit, with Paramount coming in second with only $14.5 million. MGM poured the profits back into production to perpetuate its image of luxurious glamour.

The lavish magnificence of MGM became its “house style” and applied to everything onscreen, but especially the studio’s stable of stars. Mayer had been in the movie business as an exhibitor and a producer since the 1910’s, and he discovered the power of stars early on. He believed that “The real business of making movies…became the business of making idols for the public to love and worship and to identify with. Everything else was secondary.” His almost fanatical commitment to creating and perpetuating splendid stars became a hallmark of the studio.

No other studio came close to MGM’s glamorous stars and “conspicuous construction.” Jerry Wald, a Warner Bros. writer-producer, said that his studio knew it couldn’t compete with MGM at its own game, “so we had to go after the stories, topical ones, not typical ones. The stories became the stars…We used to say “T – T – T: timely, topical, not typical.” Warner Bros. could never have created swimming musicals, but MGM was the perfect place for a movie mermaid.

When Esther toured MGM, the studio employed 6,000 people in 27 departments with a weekly payroll of $615,000. 80 writers poured forth stories and scripts to keep the 26 “stars” and 50 featured players busy, and a nearly 9,000 square foot art deco commissary kept them fed, serving about 2,700 people every day. Famous menu items included Mayer’s own family recipe for chicken soup (the chef had spent two weeks in Mayer’s kitchen learning from Mayer’s wife, Margaret), and a wonderful chocolate malt. But actress Janet Leigh recalled being too starstruck to eat: “What a sight. I could never eat, I was too busy gawking. In that huge room—God, I was always so self-conscious walking to a table—I’d see Clark Gable in one corner, Elizabeth Taylor and her mother in another, Gene Kelly tucked against the wall, and on and on and on.”

Besides the most glamorous cafeteria in the world, MGM had all the comforts of a neighborhood, including an on-site barbershop, newsstand, and a bookie named Rudi. The studio had a first aid department, a dentist, and a chiropractor, as well as a fire department and a police force of 50 to keep things orderly. There was even a schoolhouse filled with precocious youngsters like Margaret O’Brien, Elizabeth Taylor, and Judy Garland, who by law had to spend four hours of each day in school even when working on a film.

Administrative buildings housed accounting, legal, insurance, and publicity departments, and hundreds of offices and editing rooms were sprinkled across the lot. Decidedly unglamorous warehouses and vaults housed the equipment needed to capture all of the movie magic, and an enormous lab could print 150 million feet of release prints every year. But before filming ever began, intense preparation took place in the sound stages, rehearsal halls and dance studios, as well as a nearly 10,000 square foot scoring stage.

These rooms were constantly filled with some of the greatest performers in the world, including the music department’s composers, arrangers, and musicians. The sound and special effects departments hummed along nearby, recording, dubbing, and magicking MGM’s output.

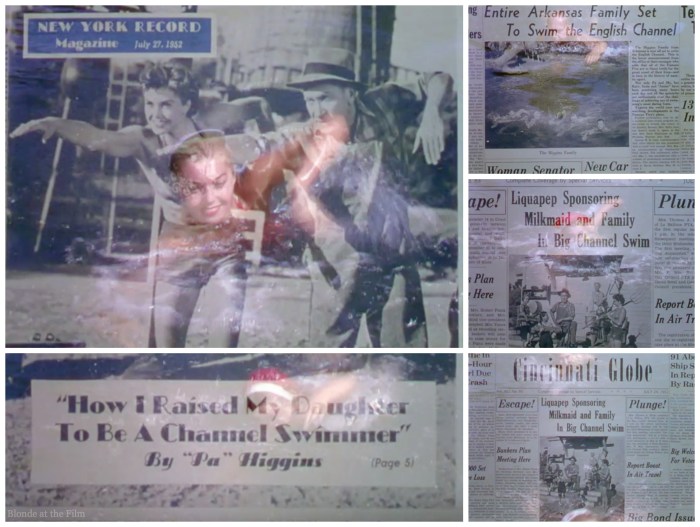

The art department employed scenic artists and plasterers who executed the designs dreamed up by 17 art directors, four assistant art directors, 43 draftsmen, and 10 sketch artists. The sets were beautifully dressed with custom-made draperies sewn by studio upholsterers, plastered with posters, or strewn with newspapers churned out by the print shop. Doorknobs, hinges, and latches were provided by the fixtures department, and props and furniture came from MGM’s unparalleled collection, which grew by about $1 million worth of objects every year in the 1940s.

When preparing for Marie Antoinette (1938), a film that has come to symbolize MGM’s obsessive, lavish extravagance, the head of the prop department, Edwin B. Willis, spent three months in France on a buying spree for the film. He purchased antique furniture, statues, paintings, objects d’art, and even original letters; when the shipment arrived it was the largest single collection of antiques ever received at the Los Angeles Harbor Customs office.

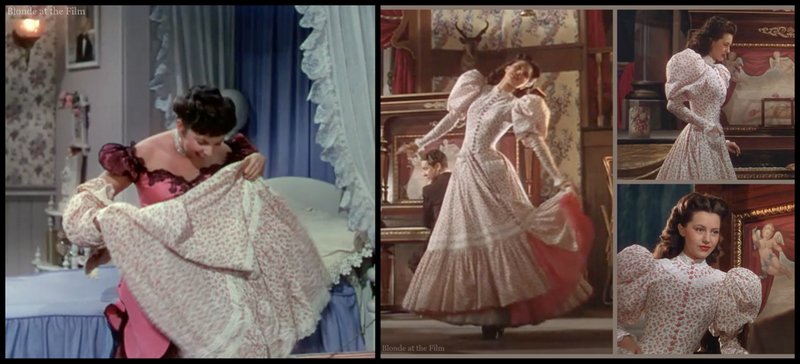

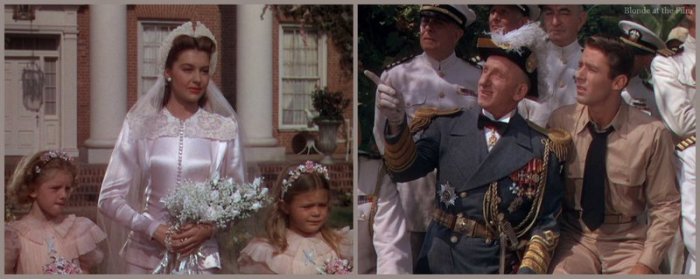

Just as much attention was lavished on the actors appearing in these sets. When Esther toured the studio in 1941, the costume department had a staff of 178 people and over 250,000 costumes stored in 15 warehouses. The enormous costume collection was constantly increasing; about 100,000 yards of material were cut and worked each year. The costumes were beautifully custom made from the most luxurious materials; no expense was spared in the name of glamour.

Costumes were often repurposed for other films, usually on background performers. (A favorite pastime of mine is catching these recycled costumes…)

Some of the best designers in the world worked at the studios and crafted the most gorgeous clothes that have ever appeared on screen. Besides the storage facilities and buzzing workrooms, the costume department also included dozens of cubicles where starlets and extras tried on the outfits, as well as large, elegant fitting rooms reserved for private consultations with stars.

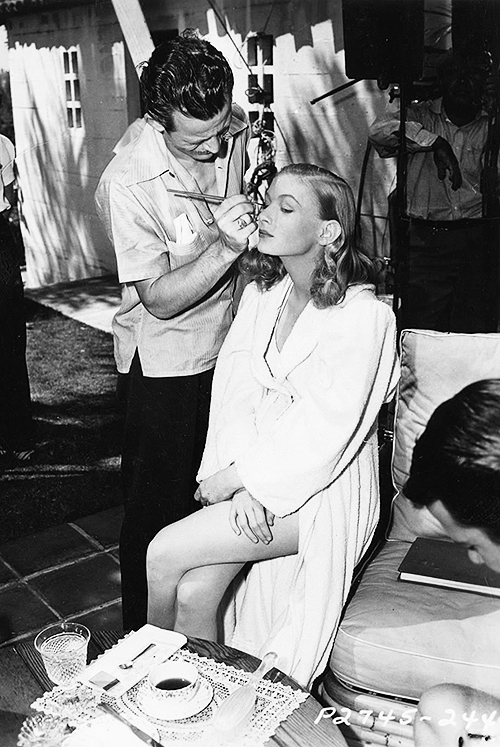

The makeup department, which also included hairstylists, looked like a swanky salon, but it could handle thousands of actors a day, and publicists boasted it could “change the appearance of 1,200 actors an hour” in the 1950s. Betty Garrett remembered that “every MGM contract player had a mimeographed photo with lines drawn on it to instruct the make up men how to improve our faces with make up, such as how to shade the nose and cheekbones. My photo was literally a roadmap of lines!”

Once the the actors were dressed, powdered, and coiffed, they usually didn’t have far to go. Location shooting was expensive, and productions that did leave southern California quickly descended into costly chaos, so the studios preferred to film in their own backyards. Claims of realism didn’t sway the studio, and verisimilitude was certainly not reason enough to leave the comfort and control of the backlot. Instead, MGM and the other studios poured a tremendous amount of money and labor into building sets and keeping them camera-ready. The studios were skilled at tweaking their sets to enable their use in dozens, if not hundreds, of other films, so investment in the backlot was generally worth it.

Such meticulous organization made the backlot a cost-effective option compared to the expensive, logistical nightmare of shooting on location. The backlots thus grew into magical, highly organized movie factories with everything and anything required to make films.

MGM boasted the biggest backlot in Hollywood with an extraordinary collection of outdoor sets where scenes set on any corner of the earth could be filmed. There was a dock with a gangplank leading to an attached, hollow ocean liner, several railroad depots, and a replica of Grand Central Station. There was a 10-acre district of specific New York City streets that were among the most used on the lot. As Gene Kelly later said of the New York streets, “Any actor or actress who made, say, more than one or two films at the studio sooner or later probably would find himself shooting a sequence here.”

There were also “small town” streets and squares collectively called the “Andy Hardy” or “New England Street,” which is where Mickey Rooney and the rest of the Hardy family lived. The backlot also included a Victorian-era street built for Meet Me in St.Louis (1944), an Army base, a castle, rose-covered cottages, a gracious country estate, and a “Southern mansion,” as well as formal parks and gardens befitting such grand houses.

One could visit a boarding school/college set, a mill house, a cemetery, a pool with a diving board, an enormous stone bridge (usually appearing as vaguely French) and very clean stables (not to be confused with the real, functioning stables on a separate part of the lot). French, Spanish, Chinese, British, Italian, Dutch, Russian, and Irish villages, streets, courtyards, harbors, and estates were scattered with geographic whimsy across the lot. A clever cut could make sets that were acres apart appear contiguous, and create a larger world than what really existed.

“Natural” sets existed, too; there were several lakes, jungles and rivers where Weissmuller’s Tarzan’s adventures were filmed. Forests, fields, and country roads along with a farmhouse with a picturesque barn provided wilderness and rural locations. MGM also boasted a huge collection of western streets and forts that were spread across 12 acres of the backlot and comprised the biggest Western set in the world. They were just plywood facades, but from the right angle, they looked all too real.

Other sections of the backlot were crowded with buildings never seen on screen. For instance, the research department was a crucial cog in MGM’s machine, but existed mostly under the radar. Housed in four buildings stuffed with 20,000 books and 250,000 clippings all tidily cross-referenced on 80,000 index cards, the department could answer 500 questions a day, and helped to guide writers, producers, and the art, costume, and prop departments, though impeccable accuracy wasn’t the top priority. For example, the 98 palace sets built for Marie Antoinette included many accurate details, but many alterations, too. Some of Versailles’ delicate moldings were actually too delicate to show up well on film, so they were bulked up on the set. More drastic changes were made, too, like the addition of an enormous staircase to create a more imposing hall. MGM was perhaps the only entity that could ever find Versailles too subtle.

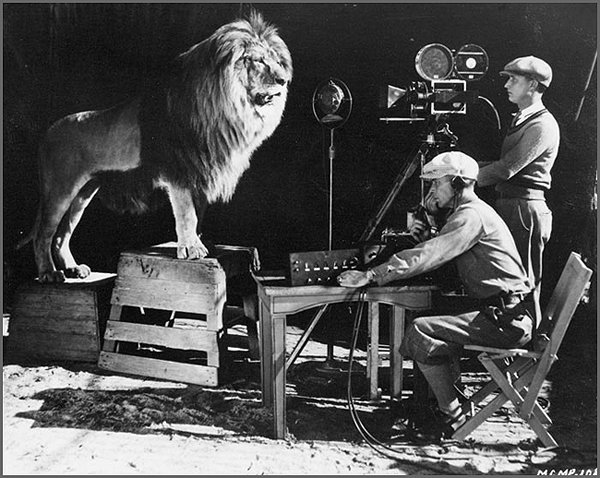

There was also a zoo where animals needed for filming lived, including Leo the lion, as well as stables for all those westerns, and a blacksmith shop. There were storage hangars, craft shops, a plant nursery and sod farm that provided plants and trees for filming, and thousands of square feet of overflow storage—necessary but dull.

A transportation department furnished limousines for executives and stars, helped move equipment and various ephemera around the lot, and also maintained and supplied prop vehicles of all kinds for filming. These drivers and mechanics were just some of MGM’s thousands of employees who never appeared on camera. The studio had a full staff of gardeners, zookeepers, welders, sheet metal workers, chemists, blacksmiths, plumbers, carpenters (500 when the studio was working at its peak), and electricians. They reported to work every day at MGM’s paint, glass, and rubber mold factories, laboratories, foundry, plumbing department, lumberyard, electric workshops, four power plants, and water tower.

With all of its departments, materials, and craftspeople, MGM seemed capable of putting anything onscreen. Jack Martin Smith, an MGM art director, remembered the extraordinary daily feats performed at the studio: “If you needed a chimpanzee tomorrow, it was sitting there. If you needed an alligator, it was there. If you needed a couple of lions, they were there. There were three or four men in the leather shop who did nothing but repair carriages and harnesses. Whatever you wanted, whatever you needed, it was there. And if it wasn’t already there, someone would make it for you.”

The action never slowed: despite the enormous size and complexity of the backlot with its sets, rehearsal halls, and editing rooms, nothing was idle, at least not for long. Maintaining such a huge operation required consistent production simply to pay the overhead. So, “Although some stars might go on suspension if they hated the scripts offered, the studio still had to carry on paying its other contract artists, whether or not there were projects that suited them. Every week in which a sound stage was empty, or a star idle, was a misuse of resources.” Meticulous planning, budgeting, and scheduling kept empty stages and idle stars to a minimum, and ensured a supply for the world’s screens.

*

When Esther Williams visited MGM that day, she probably only saw a tiny fraction of MGM’s impressive backlot and astounding staff, but her visit wisely included the star dressing rooms. These “home away from homes” featured kitchens, living rooms, fireplaces, and bathrooms, and presented an entirely different world of luxurious privacy compared to the “crummy little cubicle” she’d used at the Aquacade.

Esther was even allowed inside Greer Garson’s elegant dressing room, which was bigger than the apartment Esther shared with Leonard in Silver Lake. (MGM knew what it was doing when it invited Esther to visit!) After her tour and a meeting with Mayer, Esther began to lean towards MGM. And who could blame her? MGM presented a world so magical and marvelous that it’s no wonder she changed her mind.

MGM had the talent, the style, and the capital to produce glittering, glamorous extravaganzas, and they turned their full power on their new mermaid. What’s more, Esther seemed to know that. She understood that her movies were new, that they were dependent on lush production values and escapist fantasy, and that MGM was the only studio that could produce the kind of film that would turn her into a star.

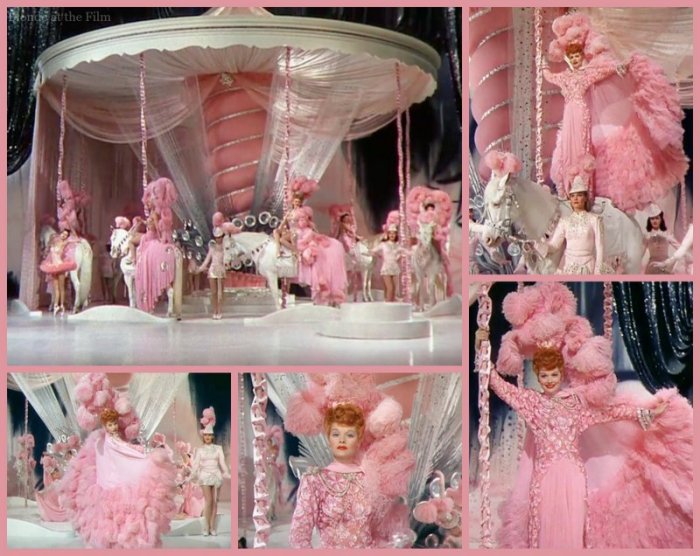

Esther returned to I. Magnin to drop off the Chanel suit before heading home to Silver Lake. Then she and Leonard went to see MGM’s Ziegfeld Girl (1941). This film was a glamour explosion, a visually spectacular, ridiculously beautifully movie even for MGM. Lana Turner, Hedy Lamarr, and Judy Garland appear so gorgeous in Adrian’s over-the-top gowns as they stroll through the big white sets that they seem almost otherworldly. All that she had seen at MGM, capped off by this movie, tipped the scales in MGM’s favor: “Suddenly, after saying no for all this time, I was starstruck. I was hooked on the possibility that all those dreams could actually come true.” Esther decided to give this movie thing a try despite Leonard’s continued disapproval.

Stay tuned for the next excerpt. Thanks for reading!

Categories: History