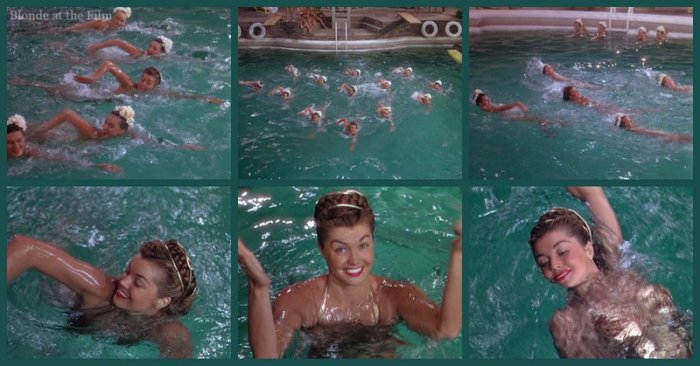

The Aquacade

This is the 6th excerpt from my biography of Esther Williams, The Mermaid and Me. You can find the other entries here. In the previous excerpt, Esther’s competitive swimming career came to a disappointing end, but her career in show business began when she was cast as Aquabelle #1 in Billy Rose’s Aquacade in San Francisco. The Aquacade was a vaudeville style revue with water, and was due to open in the spring of 1940 as part of the second year of attractions on Treasure Island, an enormous complex built for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition.

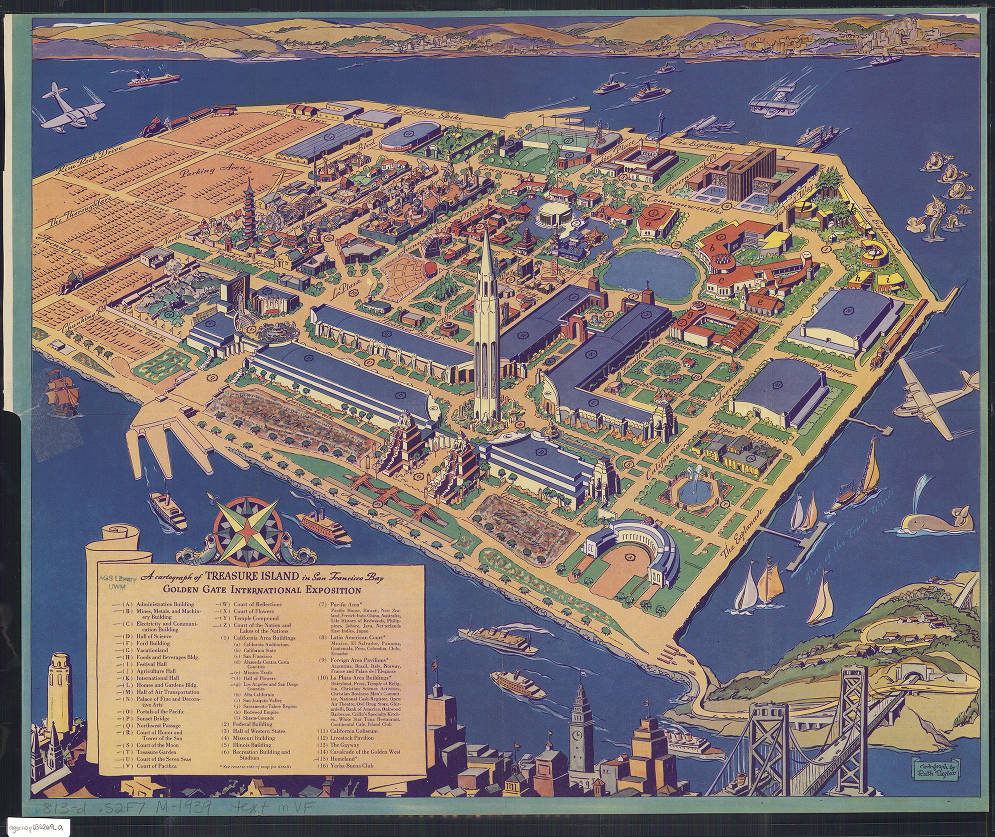

Treasure Island

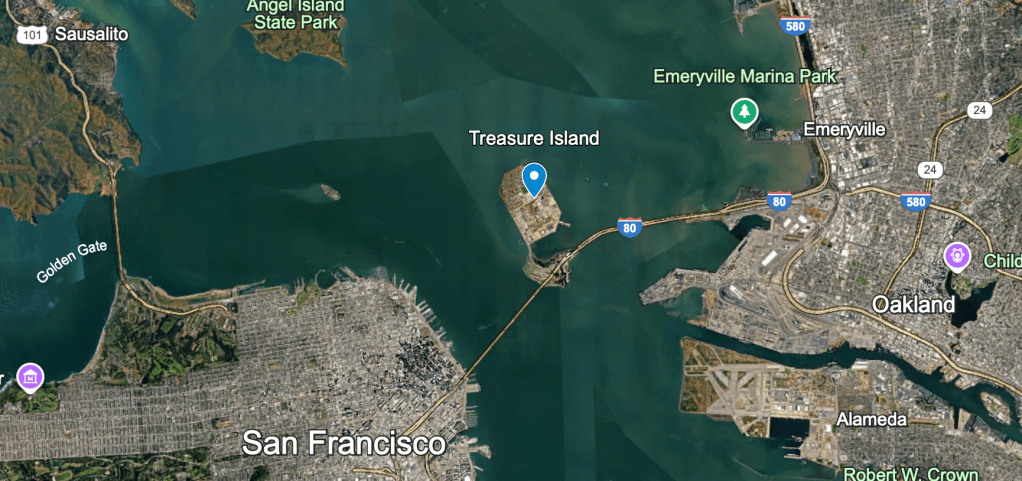

The Golden Gate International Exposition opened in 1939 to celebrate San Francisco’s two new bridges: the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. They opened in 1936 and 1937, respectively, and plans for the Exposition began in 1933. It was an enormous undertaking; besides the usual construction required for a World’s Fair, the organizers added another obstacle by selecting a nonexistent site. Rather than build on available land, the Exposition was planned for a new, purpose built island in the Bay. The Yerba Buena Shoals, (a shipping hazard in the busy Bay), that lay between San Francisco and Oakland, would form the underwater backbone of the new island. Work began in 1936, sponsored in large part by WPA grants because the city intended to use the island as an airport after the Exposition. The artificial land mass, which they named Treasure Island, quickly rose from the water thanks to twenty million cubic yards of sand dredged from the bottom of the Bay, as well as almost 300,000 tons of rock added to the site. The “land” that had so recently been the sea bottom was then processed to remove the salt and covered by 50,000 cubic yards of loam to enable plant growth.

When complete, the 385-acre island was roughly rectangular in shape and measured about a mile long and two-thirds of a mile wide. It was attached to Yerba Buena Island at its southern tip, and fairgoers could reach the island by boat, plane, or car thanks to a 900-foot causeway that linked the island to the San Francisco-Oakland Bridge where it crossed Yerba Buena.

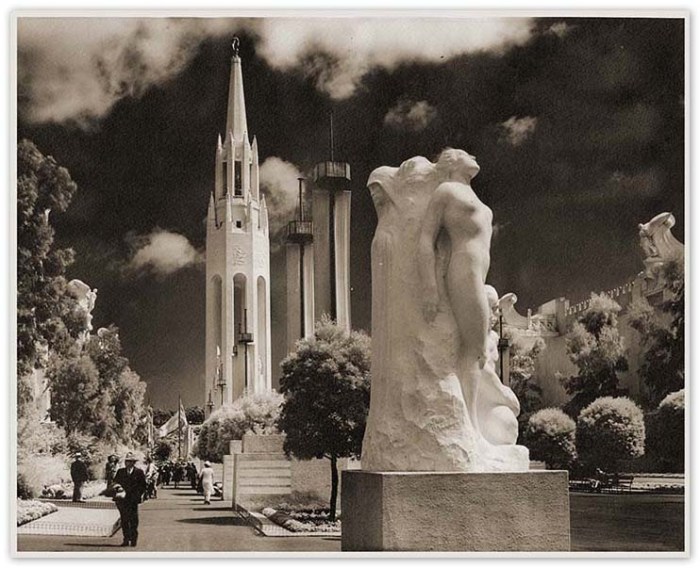

Once the troublesome shoals had been transformed into Treasure Island, construction began to turn this virgin land into a showplace worthy of a World’s Fair. The Exposition took the shape of a walled city with a grand Central Court featuring a 400-foot tall “Tower of the Sun.” Avenues branched off from the Central Court and led to various other plazas and pavilions. At the southern end of the island was the Port of the Trade Winds where ships of all kinds, including junks and yachts, were docked.

A stroll north along the Avenue of the Seven Seas brought you to the Court of Pacifica, named for its 80-foot statue of the goddess of the Pacific Ocean. That end of the island also held a 12,000 car parking lot and a 40-acre amusement park called the “Gayway” with rollercoasters, rides, and shows, including the popular Sally Rand’s Nude Ranch and monkeys driving cars around a racetrack. A wide boulevard encircled the island and featured attractions such as Chinese City, Hollywood Boulevard, and Streets of the World.

Pavilions and halls sprinkled across the island showcased art, industry, and technology, including demonstrations of a newfangled invention called television. Over forty countries sent items to the Fair, but the US and California received special attention. For example, visitors could walk along a huge, million dollar (roughly 22 million in 2025 dollars!) relief map of the United States, and California and its counties had their own pavilions.

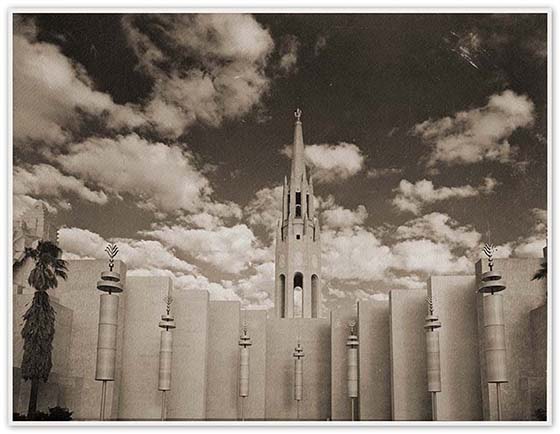

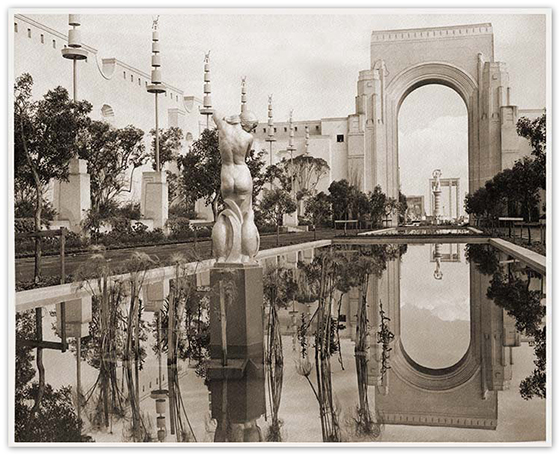

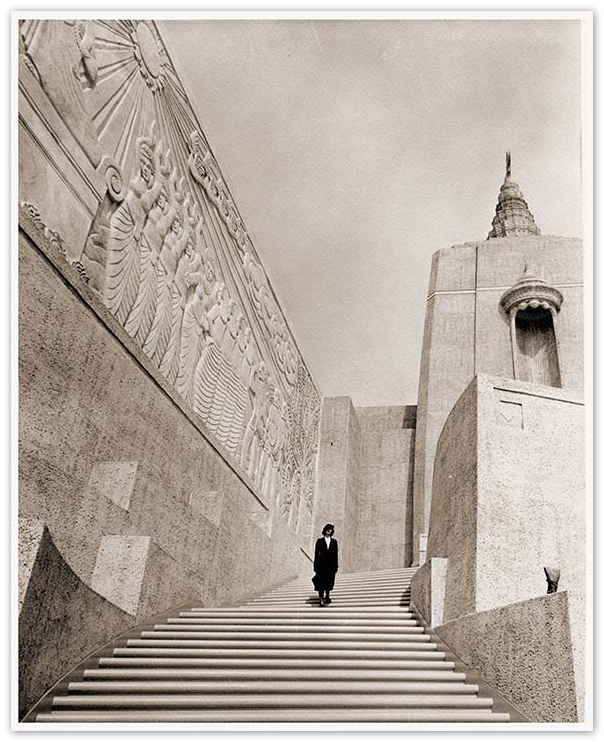

The architecture of the entire complex reflected the Exposition’s “Pageant of the Pacific” theme. Everything was built and decorated in a new style called “Pacifica” that incorporated elements from both sides of the Pacific, though geographically incongruous elements from Mayan and Incan art were also included. You could find pilasters “reminiscent of Angkor Wat,” Malayan-inspired pyramids, stylized statues, reliefs, murals, and temple-style buildings all reflecting southeast Asian architectural tropes with a California twist. The style leaned heavily on the ancient and even prehistoric animal sculptures inspired by the La Brea Tar Pit excavations, though everything was slightly streamlined to fit the modern age.

The landscaping was extraordinary, too; lagoons and fountains were everywhere, and over 4,000 trees, 70,000 shrubs and 700,000 flowers were planted for the Fair, including many rare, tropical varieties including orchids, hibiscus, palm trees and citrus trees. As if these stunning blooms weren’t show stopping enough, state of the art lighting effects turned the place into a shimmering “magic city of light.”

According to a contemporary article: “The island’s colors, stimulating, unforgettable, represent the first extensive application of chromotherapy—the science of health treatment by color usage. In the daytime the effects are gained with flowers and tinted walls; at night, with fluorescent tubes, with the new ‘black light,’ with ultra-violet floods, underwater lamps, translucent glass fabric pillars, and cylindrical lanterns 75 feet high. Some of the flower beds are played upon by artificial moonlight, others bathed in sunshine created out of neon and mercury. The $1,000,000 illumination program presents at nightfall the illusion of a magic city of light, floating on the waters of San Francisco Bay.”

The reporter wasn’t exaggerating; thanks to the 10,000 floodlights on the island as well as two dozen 36-inch searchlights on the strip of land connecting Treasure Island to Yerba Buena, the Exposition was visible for 100 miles. Even some of the buildings glowed: a special stucco made with vermiculite (a mica-type substance) made immense, seventy-foot walls iridescent. Their phosphorescent glow wasn’t enough for the Fair, so the effect was accentuated with colored floodlights.

Treasure Island’s geographic isolation made the lighting design an engineering as well as an artistic feat. The Fair required forty million kilowatt hours for its forty weeks of operation (or enough to power over 3,000 modern homes for a year.) Electricity was supplied through three enormous, 9,000 foot-long underwater cables from the mainland, and power was then disseminated through 35,000 miles of cables. (All this for a 400 acre island!)

The 1939 Fair

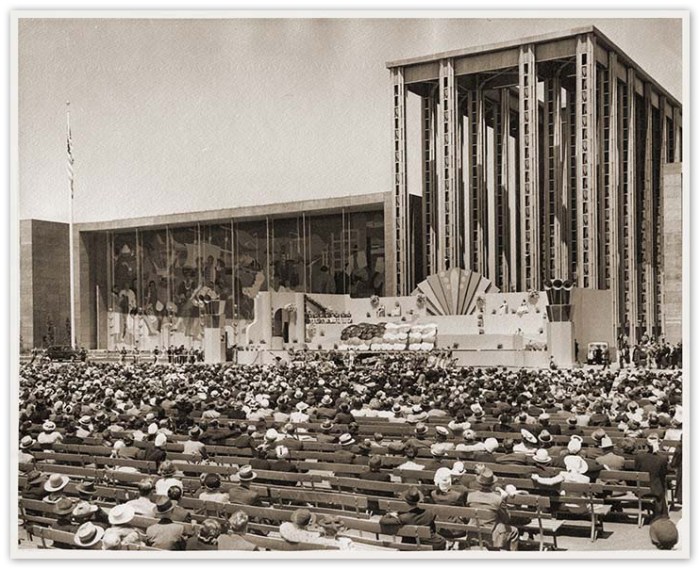

The Exposition was quite the event: President Roosevelt gave a radio address at the Opening Ceremonies on February 18, 1939, the Fair was promoted in newsreels and print media, and the popular Charlie Chan film series set an entry during the Fair. Some of Charlie Chan at Treasure Island was filmed on location in the spring after the Fair opened, and the movie premiered that September. Esther Williams didn’t attend the Exposition in 1939, but it wouldn’t be surprising if she heard the President’s speech, saw a newsreel or two, or encountered the Charlie Chan film. But she could never have imagined starring in one of the Fair’s biggest attractions!

But her arrival was still months away. The Fair set one-day and weekend attendance records of 187,730 and 274,359 visitors, respectively, in October, though its total visitor count barely reached half of the 20,000,000 people the organizers had estimated would attend. The Fair closed on October 29th, 1939, but talks almost immediately began to open Treasure Island the next spring. Despite a mostly successful run and an estimated influx of $100 million to the region, the Fair had failed to turn a profit. Many of the organizers hoped that another several months would bring them out of the red.

An opening date was set for May 1940, ticket prices were lowered to 50 cents, and the grounds and buildings were given extra oomph to bring in more visitors. As one article about the 1940 re-opening stated, “Do you remember the first time you saw Treasure Island by night: the unearthly beauty of courts, pavilions and gardens as painted in glowing colors by hidden lights? That impression remains fixed in the minds of every visitor as an experience in sheer beauty not likely to be equaled in our time.”

But it’s gotten even more glorious, he promised: “This year you will find the same rainbow beauty reflected from walls and fountains under the more prosaic sun, for color–and more color–is the keynote of the 1940 Exposition.” The island’s 1939 color scheme was amped up with splashes of coral, chartreuse, violet, gold, and green, and at night, the island fought off darkness with huge neon signs advertising the attractions amongst the extravagant lights of the “magic city.”

New attractions were added, too, with an emphasis on entertainment rather than the previous year’s focus on museum-style exhibits. The new “Art in Action” exhibition featured live demonstrations by artists such as Dudley C. Carter, Frederick E. Olmsted, Herman Volz, and Diego Rivera, who began his mural “Pan-American Unity” at the show. The Folies Bergere, a dance and comedy show with plenty of pretty girls in skimpy costumes, completely revamped its production for the new season, and a famous puppet show called Salici’s Puppets set up in the Hall of the Western States. But one of the most anticipated new attractions was Billy Rose’s Aquacade, which had become the most successful show at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

The Aquacade

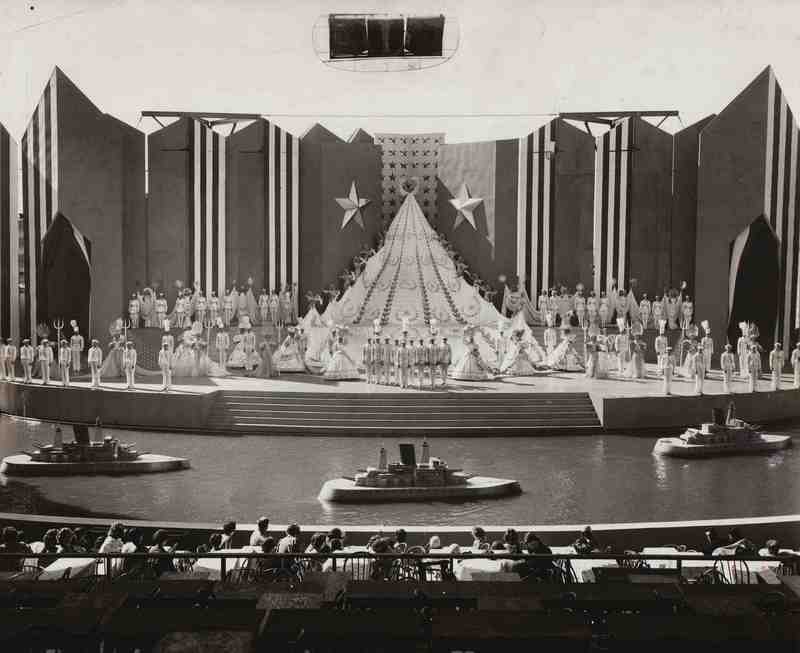

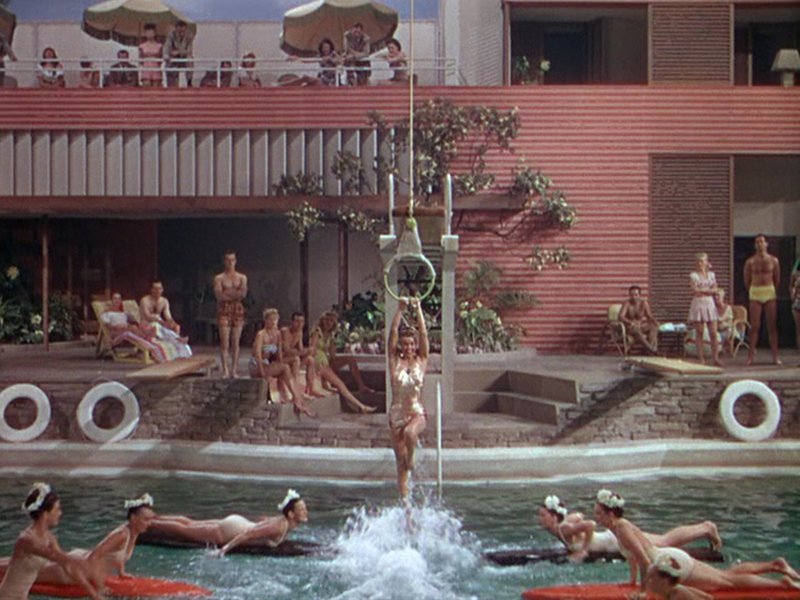

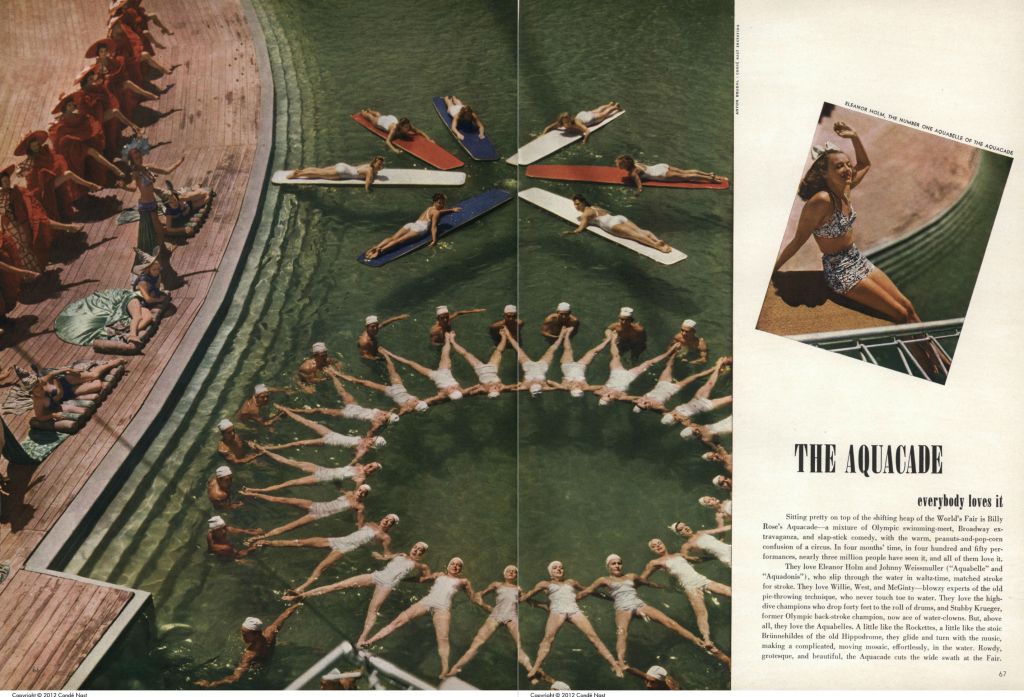

Billy Rose was a notorious nightclub owner, songwriter, and showbiz impresario who had first produced the Aquacade in Cleveland at the Great Lakes Exposition in 1937. The show was essentially a vaudeville revue with water, a Ziegfeld Follies with bathing suits instead of gowns, and choreographed dives and swimming instead of staircase struts and dancing. A full orchestra, comics, singers, and dancers performed on a stage on the shores of Lake Erie, and famous divers plunged into the lake in daring exhibitions. A chorus of male and female swimmers known as “aquadonis” and “aquabelles,” or “aquacuties,” delighted the crowds with “water ballets,” or what would later become known as “synchronized swimming.”

Rose landed a huge star as Aquadonis #1 for the 1937 Aquacade: MGM’s Tarzan and swimming legend Johnny Weissmuller. Weissmuller was a champion swimmer who had come to entertainment after a successful racing career. He won a total of five gold medals in freestyle events at the 1924 and 1928 Olympics, as well as a bronze medal with the water polo team in 1924. He held dozens of national and international records, and he retired from competition unbeaten. Then he played Tarzan in MGM’s Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932 and became a star overnight.

Opposite Weissmuller as Aquabelle #1 was Eleanor Holm, the 1932 gold medalist in the 100-meter backstroke. In 1936, she was kicked off the 1936 Olympic team for getting drunk, and this scandal turned her into something of a celebrity. So she turned to show business professionally. She would star in one feature film, Tarzan’s Revenge (1938), (though this Tarzan was played by Glenn Morris) but otherwise stuck to live shows.

The Aquacade was a success in Cleveland, so Rose restaged it for an 11,000 seat amphitheater overlooking Meadow Lake at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. Just as in Cleveland, Rose hired Holm and Weissmuller as his leads, though now Holm was Rose’s wife. (The pair married in 1939 after he divorced Fanny Brice and she divorced her bandleader husband, Art Jarrett.) Once again, the show was a hit. Vogue described the Aquacade as a “mixture of Olympic swimming-meet, Broadway extravaganza, and slap-stick comedy, with the warm, peanuts-and-pop-corn confusion of a circus.” It was “rowdy, grotesque, and beautiful…” and “everybody loves it.”

Unsurprisingly, the Golden Gate Exposition was interested in hosting its own Aquacade after the show’s success in New York. So Rose left the Aquacade running for the second season of the New York Fair (financial reasons had pushed that Fair to stay open for another year, too) and started a second show on Treasure Island. This would be the third Aquacade for Rose, but the first without Holm, who stayed with the New York show. But Weissmuller came out west with Rose to anchor the new production.

Massive and speedy renovations turned the International Hall just south of the Gayway into a home for the Aquacade. An article in San Francisco Life detailed the construction in awed terms:

“Here is one undertaking that a press agent can call colossal and still be guilty of understatement. So gigantic is the auditorium that a gang of tractors, bulldozers and scrapers excavating the 50×150 swimming pool were almost lost in the gloom. First time I ever saw a major excavating job going on indoors! Scaffoldings are going up to hold the lighting platforms –- and Lincoln Dickey [Fair impresario and frequent collaborator with Rose] says there will be more spotlights used to light this show than were ever gathered under one roof before. The seats are not in yet. There will be 7,000 of them and it seems to me that all will have an excellent view of the stage and tank.”

A few weeks before the Exposition opened for its 1940 season, Esther stepped off the train from Los Angeles and began rehearsals at Treasure Island. One can imagine how overwhelming and surreal the situation was. She was eighteen, newly on her own, and about to undertake something entirely unfamiliar. Plus, the setting was a tropical fever dream, a strange paradise of Pacifica on a fake island. The colors, lights, and architecture were unlike anything she had ever seen—that was the point, after all. A World’s Fair was supposed to be utterly unique and over-the-top; a dreamlike mix of historical homage, futuristic technology, carnival attractions, and stunning surroundings designed to impress. Added to all of that, Esther was supposed to star in a water show opposite Tarzan when a week ago she had been a (mostly) anonymous shopgirl.

Fortunately, there were at least two familiar faces on Treasure Island. Esther’s LAAC teammate Virginia Hopkins, with whom she’d set so many relay records, and Virginia’s twin sister Marian were featured performers in the Aquacade billed as the “Hopkins Twins.” But national and world champion diver Helen Crlinkovich, another Los Angeles girl who had crossed paths with Esther at many swim meets, was asked to perform in the show but declined as she wanted to keep her amateur status. (She would later appear as Esther’s stunt double in Easy To Love (1953).) Another indirect movie connection was Gertrude Ederle, gold medalist in the 1924 Games and the first woman to swim the English Channel. Ederle was a featured performer at the Aquacade. Of course, Esther could not know at the time that in about a dozen years she would “swim” the English Channel in the film Dangerous When Wet (1953).

Stay tuned for the next excerpt from The Mermaid and Me!

Categories: History

Great writing and fascinating information. Very impressive.

Thank you so much!

WOWâ¦very interesting information about Treasure Island. I never knew this piece of history, although Iâm from Eastern Washington, so can be forgiven for never paying too much attention to San Francisco history. I actually looked on âGoogle Earthâ at their satellite photos and they have an early image from July 1946 (although that was a plane photo Iâm sure, not satellite). I assume the Navy hadnât made too many changes since 1940, but it is interesting to compare the most recent image (July 2025) to the earlier image. A couple objects (down at the southern part of the island) still remain, but for the most part, obviously a lot has been modified. It is a good thing that the military took over and it wasnât made into an airport. Todayâs modern SFO has about a two mile runway. Treasure Island is only about a mile long, so it wouldnât have done well as an airport for jets!!

But a fun piece of history you uncovered for me! I appreciate your writings!! Please continue!

[cid:image002.jpg@01DC32C9.5DE81B60][cid:image004.jpg@01DC32C9.5DE81B60]

Thanks for this comment! It was a wild undertaking but it seems as though the island has been used ever since in different ways. Thanks for reading!